[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T. J.[/dropcap] Clark comes to London to shed new light on Picasso and ‘truth’.

This autumn, acclaimed art historian T. J. Clark has been travelling around London giving talks about his latest book Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica. In this book Clark concentrates on the artwork Picasso produced during the 1920s, which has been considered not to be the artist’s best period.[quote]Clark interprets Picasso’s

output in the 1920s

as a time marking

the end of intimacy

and proximity – the end

of ‘close-ups’ to things

one knows in daily life.[/quote]

Indeed, Greenberg calls the results of this artistic epoch a failure of nerve. Other scholars have criticised Picasso’s art at this time in terms of its ‘brightness’, condemning it as overdone. Clark conveyed that he wanted to re-address the 1920s because it is neglected and misunderstood. The motive fits well with his well-known desire to re-address the methodologies and focuses of the history of art in a new type of Social Art History.

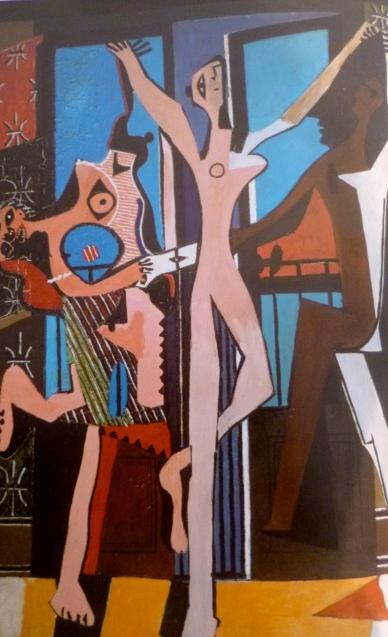

Clark concentrates on three particular paintings in his central chapters. The first, ‘Guitar and Mandolin on a Table’ 1924, which he renames ‘Still Life in Front of a Window’, is the largest still life Picasso ever did. Next to be considered is ‘The Three Dancers’ made in 1925 – a painting Picasso said was his best, or better than ‘Guernica’. This is renamed as ‘Young Girls Dancing in Front of a Window’ in Clark’s book.

Pablo Picasso ‘Guitar and Mandolin on a Table’, Detail. Taken from Clarke’s book.

Pablo Picasso ‘Guitar and Mandolin on a Table’, Detail. Taken from Clarke’s book.

The last central painting addressed is ‘The Painter and His Model’ 1927, which is by far the least well-known work of the three. The renaming of the paintings to locate the subject matter within rooms and to include window references is important for Clark’s argument, as I hope to illustrate later.

Monstrosity

Clark interprets Picasso’s output in the 1920s as a time marking the end of intimacy and proximity – the end of ‘close-ups’ to things one knows in daily life. He also sees it as the end of ‘coolness’. This period allows for an exploration into what happens to life after the end of WWI. Clark argues that Picasso turns to monstrosity, giving a monstrous view of the human condition. However, Clark also states that monstrosity is combined with tenderness.

From this complex and possible oxymoronic position, the 20th century appears by implication rather than direct reference in Picasso’s paintings (Clark argues that ‘Guernica’ is a special and anomalous painting of the time because it does obviously use direct referencing).

Clark proceeds by pronouncing that the way the 20th century conditions appear indirectly is through being manifest in strange and disturbing things being done to, and by, the body in the familiar space of the room.

Nietzsche

Clark then states that the only satisfactory way of looking at these paintings is by drawing upon the philosopher Nietzsche and his ideas of truth in On the Genealogy of Morals. This is partly because post-WWI saw an end in the long belief in ‘truth’. Nietzsche thought artists, actors and generally modern artistic people would know that it had ended and would search to put a new, valuable thing in place of truth. He anticipated that this process would be painful, horrific, and hard.

From this, Clark poses the question of whether Picasso is the artist of ‘untruth’ and so the modern artist that Nietzsche was looking for. In this way, Clark investigates how much Nietzsche’s philosophy of the end of truth applies to Picasso’s work. He also questions whether this could end up as an aesthetic strength. Overall, Clark argues that Picasso attempts to depict the Untruth we all live in.

Untruth

Clark insists that in Picasso’s 1920s paintings, Untruth is “the outside coming into the room”. In the talk, he went on to describe how this is so in the painting, ‘The Three Dancers’, by mostly looking at formal aspects of the work. For example, he emphasised the importance of the colour blue. Blue hues represent the outside, which creates an oppressive atmosphere because blue is a recessive colour and yet it comes forward in this painting.

Literally, the outside is brought inside. Additionally, as blue is the unknown ‘outside’, ‘nowhere-ness’ is written into the colour. This outside coming in produces the effect of defamiliarisation and strangeness. Clark also suggests that the blue hues takes part in the three dancers’ performance, it animates and shapes them.

Detail: Pablo Picasso, ‘The Three Dancers’, taken from Clarke’s book.

Detail: Pablo Picasso, ‘The Three Dancers’, taken from Clarke’s book.

By considering the colour blue in multiple ways, Clark concludes that it is not just one thing; blue cannot be pinned down, defined, made familiar.

Nietzsche advocates that we enter a ‘higher order’ when things cease to be familiar. Clark states that this idea can be related to Picasso because he defamilarises things in order to reveal the ‘Untruth’ of human life. In fact, Picasso sees the incalculable, the strange, and unfamiliar as part of everyday life and so feels it should not be presented as obscurity, mystery, or a dark unconscious.

In this way, Clark argues that for Picasso, unreality is the human condition (which reminds us of Plato’s cave).

Thinking about it another way, Clark stated that for Picasso, ‘truth’ is a room. By this he means ‘truth’ is a world that we can understand and where everything feels close, familiar, and part of the everyday. The inclusion of the room in Picasso’s painting stands as the intimate, possessable little world that we make for ourselves. In the showing of it, Picasso also shatters it right in front of our eyes.

One other idea in Clark’s talk also stood out, and this was his argument about why Picasso turned away from using collage when others around him were using it with the belief it was the ‘modern language’. Clark proposed that this was because collage is a work made by things jarring together on the flat, which was too playful and joyful for Picasso.

Collage conveys excitement in a world of debris. Things juggle on the surface, whereas Picasso wanted to contend with a ‘thick’, deep and dark surface where a fight could go on (such as between truth and untruth, light and dark, inside and outside, and hope and decay).

T. J. Clark was an engaging and highly eloquent speaker, and answered the many questions posed by the audience with great interest. It was easy to get swept up and carried away by his speech, and so not to interact with it critically. However, there are issues with his argument and areas to question.

[quote]a slightly narrow-minded

or predictable reading

of Picasso’s work[/quote]

Relying heavily on just one philosopher has the potential to produce a slightly narrow-minded or predictable reading of Picasso’s work. Maybe this also causes Clark to read social history of 1920s in a prescribed way where he is always looking for, and emphasising, examples indicating a loss of belief in ‘truth’. It does, as the Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones says, impose a historical structure on Picasso.

Also, by conglomerating society together in this struggle between truth and untruth, this can paint a monolithic view of this society, which is possibly surprising considering Clark is a Marxist. Maybe this suggests he is not Marxist enough. Another point to critique is his concentration on the social history because it could result in the paintings themselves being decentralised.

Formal properties

However, Clark does attend to the formal properties of the artworks and (particularly noticeable in his extensive concentration on the colour blue), and help us give them our attention. Instead, I feel that one of the central reasons Clark’s discussion can be deemed problematic is because he still concentrates on relatively well-known paintings.

He is re-inscribing the ‘canon’ of modern painting and accepted views of Picasso’s life and works. Essentially, Clark is still discussing the Picasso that we know, so maybe his book is not quite as radical as we are first made to believe.

Helen is an independent art critic and curator with an MA in The History of Art from UCL. Her research interests include nineteenth-century French art and ephemeral objects, Rodin’s sculpture and his developments in photography, and contemporary studio craft. She also keeps a blog – helencobby.wordpress.com and a Twitter account: @HelenCobby

![L'Esprit comique [Der komische Geist], René Magritte, 1928. Courtesy Sammlung Ulla und Heiner Pietzsch, Berlin © 2025, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo Credit: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin](https://b276103.smushcdn.com/276103/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/ew11_0098489_2025-05-12_web-140x174.jpg?lossy=1&strip=0&webp=1)