Deep into the digital era, it is hard to comprehend the pressure facing a local ‘what’s on’ focused freesheet. What supports them? The simple answer is community. So what makes a good one, and what are the ties that bind communities to a group voice that represents them?

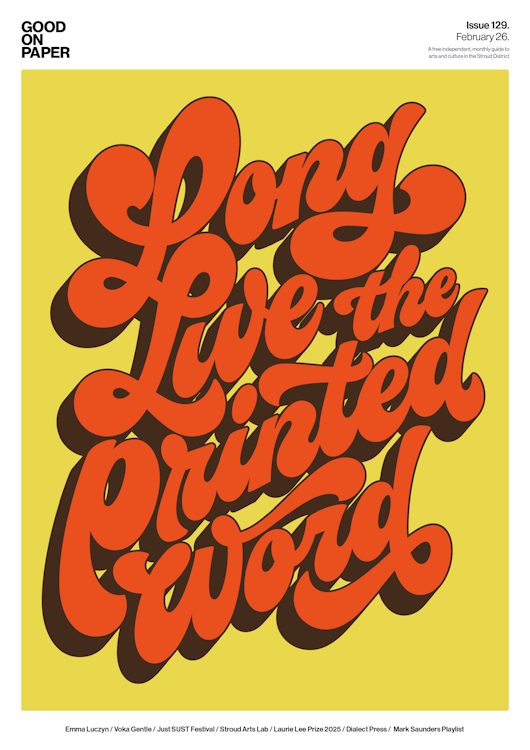

Research by Press Gazette (Majid 2021) found that at least 400 independent local news titles operate across the UK, not owned by major regional publishers. As such, one would expect them to be quirkier and more stylistically regional. A good example is Good On Paper, which serves the burgeoning creative Stroud District.

Founded in 2015 by Alex Hobbis (editor) and Adam Hinks (design), Good On Paper has so far declined to create an online version, celebrating the history of street press and seeking to get people out into the town’s galleries, cafés, venues and pubs. With its creative focus, Good On Paper has a strong catchment of readers and sponsors from lifestyle and creative partners. The publication often strengthens its links with the community by running events itself.

Matt Abbott, deputy director of the Independent Community News Network, archly observed that independent local publishers are now ‘recognised as an essential part of the media ecosystem, which [they] previously [weren’t]’ (quoted in Majid 2021). Yet this institutional recognition perhaps reflects a top-down view. Writers like Benedict Anderson (1983), who theorised the conditions for ‘imagined communities’, explored how geographically dispersed individuals are bound together through shared textual experiences, something local readers have long understood.

In Stroud, this manifests through collaborative creative networks that extend beyond the publication itself. Sean Roe of Klang Tone Records articulates this interconnectedness: ‘Stroud has so many amazing creative people living here – we are immensely proud and happy to be working collaboratively with so many artists and musicians in Stroud’ (quoted in Bigwood 2025). The record shop, which was named one of the best in the world by the Financial Times (Bigwood 2025), works closely with local festivals including Neo-Ancients, Jazz Stroud and Hidden Notes (run by Good On Paper), exemplifying how print media can catalyse wider cultural ecosystems where venues, artists, shops and publications reinforce one another’s vitality.

Good On Paper‘s 11th annual party and fundraiser in 2026 was held in six locations centred around the Lansdown Hall, including the hall itself, Klang Tone Records, the Centre for Science and Art, the Holy Water cocktail bar and the Lansdown Gallery. In proper mini-festival fashion, it was hard to see everything. Given that the event sold out, guests had to arrive early to catch many of the smaller sets. However, if you were lucky enough to shoulder in, there were several off-centre musical acts to intrigue. Throughout the night, people raved about being lucky enough to see an artist doing something unexpected and avant-garde—while others were having a Velo pizza, being elsewhere inspired, or just taking a break.

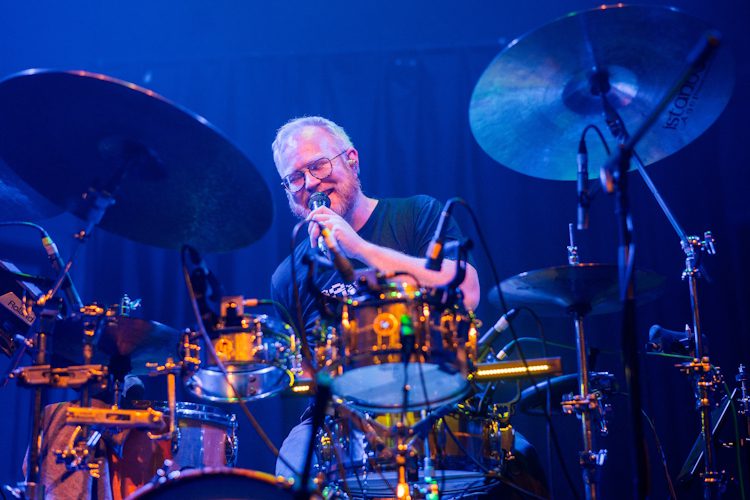

The musical highlight of the evening was the closing set by Colossal Squid. The solo work of drummer Adam Betts, previously with underground stalwarts Three Trapped Tigers, was a highly kinetic display of blast-breaks over progressive electronic chords and melodies. Unleashed by the music, the crowd let loose and with massive smiles beamed at one another: we’re here, this is great. Betts addressed the crowd, talking about his history with Stroud and the community, and the feeling of something concrete and connected. As a musical event, the fundraiser was intelligent and forward-looking. That it was this aspect that drew people together, at a time of atomised social division all over the UK, is something that should be recognised.

Alongside music, there was a WordArt exhibition featuring local creatives Mark Amis, Harvey Steele, Dan Rawlings, Eleanor Harper, Joe Magee, (Both Laughing), The Sunny Sign Co, Dennis Gould, Isobel Harper, Rooksmoor Press, Emma Luczyn, Leigh Charman, Andrew Wood and Joe Mitchell in what proved to be a clamorous affair. Crowded amongst the onlookers, it was hard to appreciate the works, and the art wasn’t really of the bombastic type to cut through the bustle and noise. Rather than focusing on landscapes, ceramics, animal portraiture or figuration—which many Stroud studios promote, perhaps as a way of generating business for classes—the exhibition displayed what Good On Paper (January 2026) described as ‘a vibrant celebration of visual language and literary artistry by Stroud District dwelling artists’. Exhibiting mixed media and operating within the remit of contemporary post-pop expression, the pieces were interesting in parts, certainly promising and good-natured, but without the grist of personal danger and bold topicality required to shout above the tipsy clamour of a packed room. In a different setting or on a different day, these pieces might have fared better. Perhaps next year there will be a wider selection of challenging art that functions within the event itself, ideally in a space that can accommodate all the curious. Despite these minor reservations, visual art, like many social activities, is measured in eyeballs, and by this metric a crowded art gallery should be considered a cultural success.

As a small event that celebrates the creative community in Stroud, the fundraiser was sold out, vibrant and satisfying. Yet with its success, one wonders whether there is an opportunity to involve the wider Stroud community. But would bigger be better? Stroud has a reasonable number of local events and festivals. Sometimes these smaller, intimate, mini-festivals create their own mini nexus of bonhomie that, once fostered and inspired, carries forward. As Raymond Williams (1958) observed, ‘culture is ordinary’, emerging not from elite institutions but from everyday practices and grassroots participation. This democratic vision, however, must be measured against questions of actual access and inclusion, concerns that cultural theorist Claire Bishop (2012) raises in Artificial Hells when she asks whether participatory art genuinely serves community or merely creates new forms of exclusion.

Local publications like Good On Paper serve communities by providing a space where people can show their ambitions and creative labours to other like-minded people. On the back of any success, questions arise as to what could have been better. Could the outreach of the event bring Stroud’s somewhat siloed tribes together? That might well sound like bureaucratic speak, but in print, Good On Paper highlights various local initiatives, public and private, and who’s to say they didn’t. It might be asked how diverse were the artists, volunteers, organisers, venues and shops taking part in the festival. Yet it’s a hard thing to measure, and while art crosses the various social vectors of any country town—rich, poor, arty, gay, hippy, hoody, punk, mums, kids, conservative or alternative (and mixtures therein)—it feels that at a certain point the democracy of doing supplants the need for symbolic signposting (See Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism, 2009). Perhaps a slightly idealistic position, which risks muting material inequality, but the sort of grassroots nourishment that fosters and is fostered by physical and conceptual spaces that bring people together around the opportunity of doing something.

It’s important to recognise that a small team planning a fundraiser can’t be all things to all people. But even within a limited remit of the possible, the Good On Paper party surpassed expectations and is evidence of what a creative vision can manifest. Moreover, it’s a celebration of what print can achieve by putting communities on the same page during the digital age.

Good On Paper Party/Fundraiser 2026. 31 Jan 2026, Stroud, UK

Good On Paper

Lansdown Hall and Gallery

Images Courtesy of Good On Paper © Jonny Barratt

Bibliography

Anderson, B. (1983) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Bigwood, M. (2025) ‘Stroud record store named as one of the best in the world’, Stroud Times, 20 January. Available at:https://stroudtimes.com/stroud-record-store-named-as-one-of-the-best-in-the-world/ (Accessed: 8 February 2026).

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

Good On Paper (2026) ‘WordArt Exhibition listing’, Good On Paper, January.

Majid, A. (2021) ‘Mapped: The UK’s 400 independent local news titles + Lincolnite and Bristol Cable on secrets to success’, Press Gazette, 5 August. Available at:https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/uk-independent-community-news-sector/ (Accessed: 8 February 2026).

Williams, R. (1958) ‘Culture is ordinary’, in N. McKenzie (ed.) Conviction. London: MacGibbon and Kee, pp. 74-92.

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. LSE Masters Graduate. Arts and Culture writer since 1995 for Future Publishing, Conde Nast, Wig Magazine and Oyster. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.