Amsterdam is like The Fall. ‘Always changing, always the same’. So said broadcaster John Peel when talking about the post-punk group’s tendency to maintain a central identity through constant line-up changes and chronic shifts in musical direction. Amsterdam is a city that creates a myriad of experiences; propelled by commercial gossip, side street discovery and the incessant threat of pedestrian death at the feet of a cyclist.

During the day the city exhibits a genteel European dignity with well-dressed people moving with familiar purpose to modern buildings, at dusk the young and trendy replace them, filling the streets with the self-conscious abandon of the times. And at night… well. At night the soul of Amsterdam is revealed in optimistic decadence, calculated risks and the incessant urge to wander.

Amsterdam Art Week crystallises this experience across the phases of the day, from the sunlit work of the Rijksakademie, to the afternoon glamour of the major gallery shows, and trailing off with the personal delights of night-time rambles through the central district with this plethora of small galleries tempting the passer-by with window displays of restrained promise. It’s within the specificities of each moment that we can approach the larger questions: what makes Amsterdam a good site for art? 2025 is a political year so how is that reflected in Amsterdam’s art? Signs of growth, signs of life? What’s next?

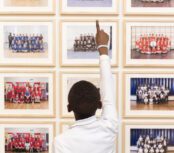

Starting the day with the Rijksakademie is a great way to orientate yourself with contemporary art through the lens of the city. Artists themselves are a reflective lens on the world around them, and the open studios – always a highlight of Amsterdam’s art scene – are a chance to experience, vicariously, the latest in art theory in practice. All the artists at the Rijksakademie have been carefully selected from around the world. The exact basis of why each artist is selected is somewhat mysterious (beyond being demonstratively talented, which is a mysterious quality in itself), and however there is a confidence in each practice that comes from room to room. Of note is that each artist on show is markedly different from each other. This points to the artists being mindful of each other, as in the wider art world there is a fair degree of commonality in output. With over 80 artists in residence, that there is little crossover, artist to artist, is an encouraging thought for the cynical reader of art. Of course certain themes are present, however there is an encouraging evolution in execution.

Artists Alexandra Hunt, Ashfika Rahman and Lucas Lugarino are three artists whose work stood out at the Rijksakademie, showing the breadth of work in the current year.

Hunt’s One Horsepower Is More Than the Power of One Horse (2025) is a meditative and engaging sculptural work, that creates an explosive tension as the heavy object, which looks a bit like an electricity bushing, is moved by the triangular position of the wires below.

‘In the exhibition, a moving sculpture of falling weights and sharp, echoing sounds share the space with an intimate waiting room of letters. Through daily readings, the artist bridges motion and stillness, overwhelming force and the quiet weight of language, inviting the audience to listen beneath the noise’ (Hunt, wall text)

Hunt’s practice uses science and scientific ideas as a social analogue, a space where our relationship to rationality, society, and material efficiency converge. By forcing the viewer to wait through the kinetic sculpture’s ‘wind up’ the piece creates an existential space, where viewers find a stillness. Contemplating the physics of the piece and trying to gauge the point when the climactic ‘start’ of the piece begins is a neat way to create an artistic experience. Prefaced well by the health and safety warnings as you enter, the promise of threat, the potential for disaster, cast a sense of action to the artist’s intentions. Which are in turn reminiscent of our current lives, lived in the comparatively peaceful shadow of conflict and disaster.

By contrast Ashfika Rahman’s installation creates a space of powerful symbolism, where drawing from stories, folklore and testimony recasts Bangladeshi history in mythic overtones. Walking into her studio the spherical arrangement of hundreds of traditional bells created an immediate sense of wonder, the interplay of scintillating light and shadows. The shadow lines and circles cast by the linear strings, individual elliptical bell mouths, and the spherical arrangement of the bells themselves is a strong motif. Reminiscent of scientific diagrams of cells, ovum crowded by sperm, but also traditional craft textures.

Rahman’s artist statement discusses social work, traditional archiving, and the discourses ‘silenced or erased’ by government policies in Bangladesh. There are many traditional uses of bells in South Asian culture, notably for ethnic, Hindu and Buddhist religious and cultural ceremonies. One interpretation of the artist’s work is that her use of traditional bells, arranged as a static cellular whole, might be read as a group of individuals, silent but casting shadows. A reading which chimes with her advocacy of marginalised communities in Bangladesh.

The artist Lucas Lugarino also engages with the concept of community, however whereas Rahman draws on South Asian history in Ghost Rococó (2025) Lugarino uses online, virtual and gaming communities as the source for his work. Still under development he describes the work as using motion tracking data as video game inputs changing the environment and telescoping action.

One of the fascinating aspects of this work is that people view work from an unmediated perspective, which as per sculpture or installation creates a particular understanding of the work depending on where the viewer is. Lugarino’s work suggests the possibility of referencing the cognitive state of the viewer by reading their body language and interpreting that within the artwork itself.

While at this stage it’s not entirely clear how effective this is in Lugarino’s work itself, as it’s still only a test version, the idea of doing so is a captivating one and opens up a number of possibilities that have roots in works such as The Ambassadors (1533) by Hans Holbein the Younger and Étant donnés (1966) by Marcel Duchamp. Art pieces that require the user to position themselves in a particular fashion to view the art. The attendant idea is that this position puts the viewer in a set way physically which has an effect on the viewer mentally. While this is probably as interpretive as not doing so, it is a form of biopolitics, as relevant as the current discourse around working from home vs working in an office. On some level if you control the body you control the mind. Creating a vocabulary of translatable human movements and associating them within the parameters of the artwork creates a dialogue with the creative work that feels like fertile territory. Lugarino is not the first to pack his wagon and head for this horizon, there are several AR and VR artists that touch on similar themes, however this sort of technology should be viewed as a new sort of paintbrush rather than an artwork in itself. As always the proof is in the aesthetic outcome.

It would be difficult to name any one, or three, best artists at the Rijksakademie as the general quality this year is particularly high. However these three artists in their way demonstrated a few key trends. Kinetic physical works, such as those by Hunt, where physical processes are used as social or emotional analogues; enculturated works that use a symbolic material or objects as material, replicated and multiplied like in Rahman’s work; and Lugarino’s use of digital virtuality to question the art premise of viewer/creator. Each of the artists show that within these trends there is still a vitality in what art can achieve. Moreover, it shows that the Rijksakademie remains committed to its aim of creating ‘the conditions for artists to thrive, and to keep reimagining the transformative power of art.’

Buoyed by the immersion of this new wave of art, Amsterdam Art Week has a number of places where established artists further the conversation. Like most major cities, art appears in a variety of hotels, public spaces, institutions and private collections are on show, with their best pieces put forward for the traveller to see as they sip a cocktail. Getting to them is a simple matter. Amsterdam is easy to travel around, the metro (GVB) serves most areas of the city and besides the majority of Art Week is centrally located which makes for a nice walk between galleries.

The galleries themselves are a mixed bag, while the passion is clearly high with every exhibition the shows themselves are extremely variable in quality. Refreshingly so. Part of visiting art galleries is finding what you like, and getting to grips with what leaves you cold. Without a proper sense of completion and execution some works have to contain something compelling to reach an audience. Press releases might dress the work as ’emphasising materiality and process’ but aesthetics matter and in 2025, the naive, the automatic, and the unrefined appears, well, sketchy. Like the bad singer on a reality show with a heart-rending backstory, it’s a formula that becomes an over-saturated trope if that background doesn’t convey something unique. Worse, it can eclipse the narrative of the work itself.

Conversely, Aldo van den Broek’s show at Gallery Vrienden van Bavink, with his scenes of post-human anomie, painted over the backstory detritus of human manufacture (cardboard, iron, wood) succeeds because it deepens the sense of foreboding and industrial decay.

The subject of his recent works suggests a sense of entropy around the veneer of modernity. Buildings eroding into grey backgrounds, desolate office scenes, Soviet project buildings, all contrasted shapes that meld into stark shadow geometry. The layering of the painted image over a composed collage-like background of textures and materials common in the manufacturing age has a depth of textural and material referents that make his paintings a live event. Seen in person the effect has a definite yet slippery presence often teasing the industrial quality of gallery spaces themselves.

The scale and severity of his darker works such as Negative Space (2025) have a transportive quality however it’s the works of his Palimpsest Tbilisi series that you return to. The Rauschenberg-esque layering of media in his work gives the pieces a sense of mystery that ties in with the depictions of Soviet-era buildings and reconstructed materials allowing the performance of elements to sing.

The subject matter of van den Broek’s paintings is inspired by his travels to Tokyo, Siberia, and Tbilisi. Places where his observations on the ethics of modern social systems reveal the paradoxes within the underlying processes of humanity that construct such systems but inevitably erode them. A question at the heart of a global view where ruptures in society, inequality and accelerating global conflicts herald an imbalance in the processes previously responsible for the growth and prosperity that characterised the modern era.

The ramifications of the ramping up of global trade in resources, weapons, and manufactured goods has a long, though faceted, history in photography. Photography containing the subjects and their material settings, be it clothes, location, or occupation accoutrements, fixing the tone of an era in tenths of a second. From traditional lives amongst colonialism, the widening scope of war, to the settings of domesticity photography has captured the human scale of larger geopolitical events. For photographic exhibitions Foam (Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam) has a reputation for featuring interesting work from established names (Avedon, Cartier-Bresson, Newton), as well as historic collections and emerging practitioners.

Of note in 2025 is The Underground Camera, a rare viewing of secret photographs taken during the Dutch resistance during World War II. Showing seemingly ordinary people complicit in acts of rebellion, the possession of a camera would have put the photographers and their subjects in grave danger. Documenting the ‘consequences of the German occupation during the 1944-45 “famine winter” in Amsterdam’ these photos show the hardships of life and the tension of occupation. Written on each determined face is a sense of the will to survive in the face of disaster. In many of the photos it’s unclear whether the people shown knew they were being photographed, and if they did, were they being purposely nonchalant? Great photos, like great art, produce a sense of event, portentously signifying the grand movement of eras through which individuals move in ways so that we see ourselves reflected in events beyond individual control.

Travelling through Amsterdam to see art, the feeling of a wilder world comes into focus. The competing voices, histories, and visions clamour around the wanderer – it’s a hokey maxim but still true enough that we often meet ourselves most completely when we’re lost. When known boundaries shift under us and when we stumble through unknown curving routes we discover things in our most receptive state. Amsterdam Art Week offers a chance to lose oneself in art and the city itself, a state in which we can connect with the world in a direct, unmediated fashion. A chance to open our senses to other realities and get wonderfully lost amongst Amsterdam’s ever twisting artistic pathways.

Amsterdam Art Week 20-25 May 2025

Amsterdam Art Week

FOAM, The Underground Camera (De Ondergedoken Camera), 2 May – 2 October 2025

Gallery Vriend Van Bavink

Travel and Accommodation supported by Amsterdam Art Week

Spider network events:

Berlin Art Week 10 – 14 September

Barcelona Gallery Weekend 18 – 21 September

Prague Art Week 25 – 28 September

Vienna Art Week 07 – 14 November

Art Week Budapest 28 – 30 November

Lisbon Art Weekend 07 – 09 November

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. LSE Masters Graduate. Arts and Culture writer since 1995 for Future Publishing, Conde Nast, Wig Magazine and Oyster. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.