The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts has been dedicated to the Slovenian artist Dr Vesna Petresin (BSc PhD FRSA) who died in May 2025 on the eve of the biennale. According to Chus Martinez, biennale director, while suffering what would be the end of her fight with cancer, she oversaw the installation of her work and, signing it off, passed away days later. A multimedia artist of international renown, her final work encapsulates not just her career but also the themes of this year’s biennale. Making a poignant statement about the nature of utopianism, science and immersive consciousness, her piece asks us to consider our position as it relates to the future.

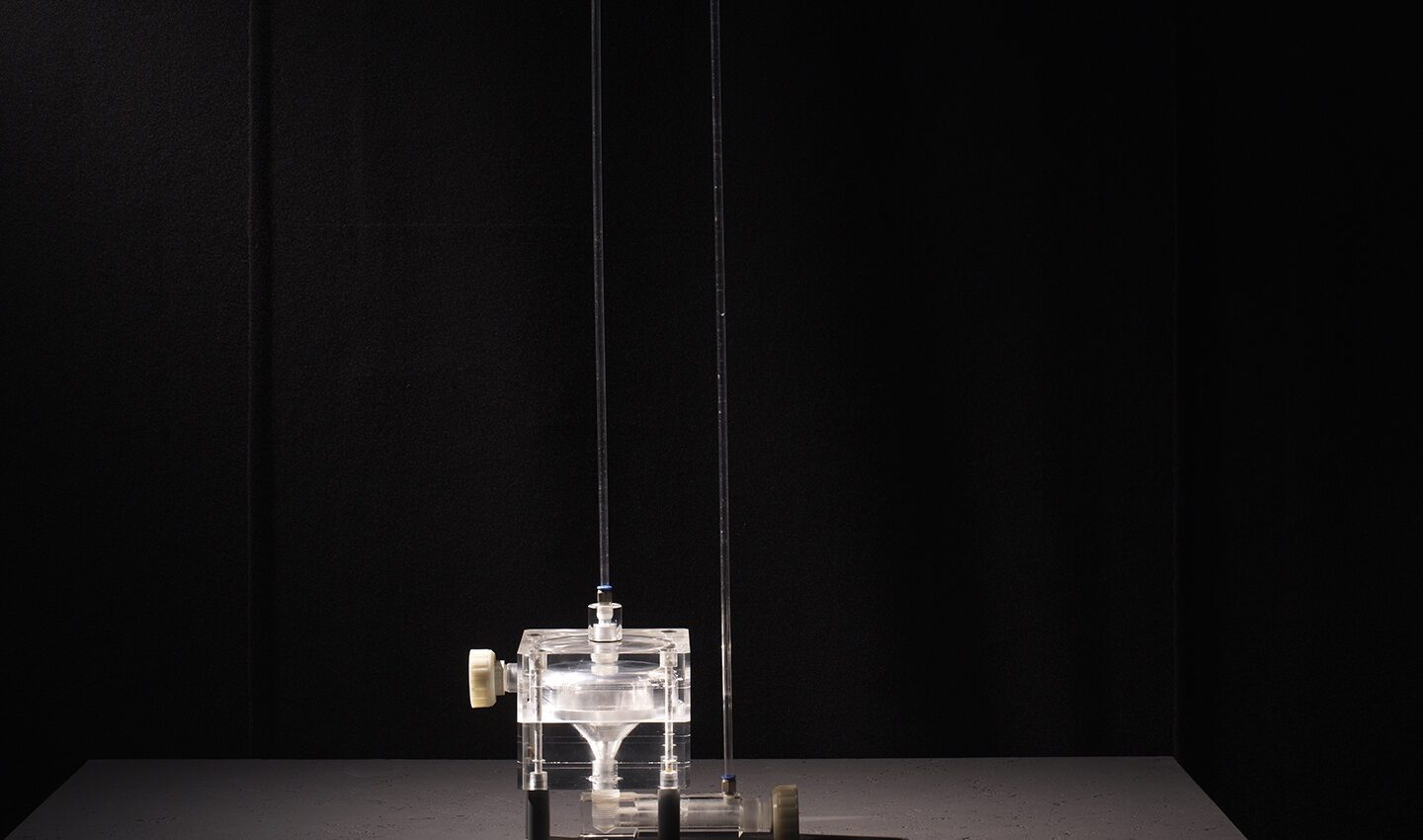

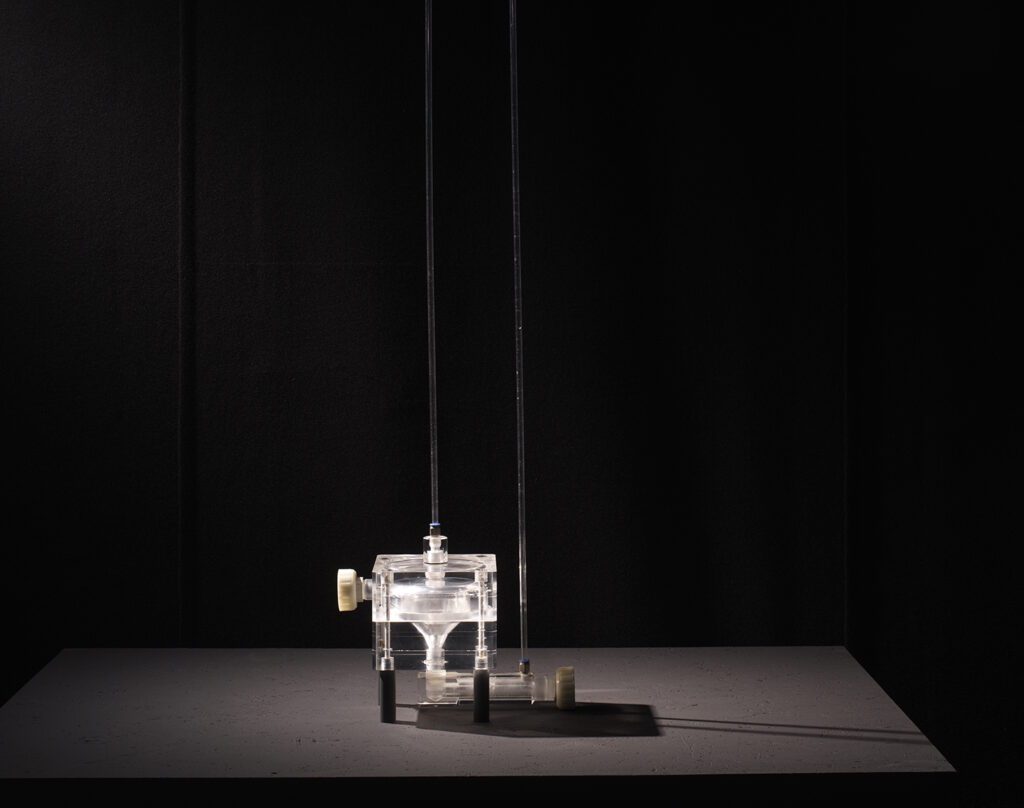

The piece Autonomous Energy Machine (2025), created in collaboration with her father Prof Dr Eugen Petrešin (scientist, see details below), contains signature elements from her career: fluid dynamics, water, generative structures, energy and synaesthetic immersion. Many of these themes/subjects were rooted in both her academic background as a student but also her continued work as an educator. Her work, as for many artists, drew on the totality of her experiences: academic, aesthetic, musical, literary and of course that shadowy source, ineffable inspiration.

Petresin studied piano, dance and singing, but graduated in architecture from the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture in Ljubljana with a PhD in the theory of composition and time in architecture. From there her career blossomed, leading to her being described by the Collide @ CERN Director & Ars Electronica Curator Arian Koek as a “transdisciplinary artist and thinker”, taking on positions such as Artist in Residence and Lecturer at the Amsterdam University of the Arts, Visiting Fellow at Goldsmiths, University of London, as well as Artist-in-Residence with ZKM Center for Art and Media.

In 2004 Petresin co-founded the London-based art collective and think-tank Rubedo (2004-2014), ‘investigating themes and techniques in aesthetics, complex geometry, optics and acoustics, through performance, installation and artefact’ (website) and had exhibited and staged performances and artefacts at international festivals and venues such as Tate Modern, ArtBasel Miami, Royal Festival Hall, Royal Academy of Arts, Venice Biennale, Cannes International Film Festival, Institute of Contemporary Arts London, CERN, Sydney Opera House, Vienna Secession, Deutsches Museum, World Architecture Festival and Beijing Architecture Biennale.

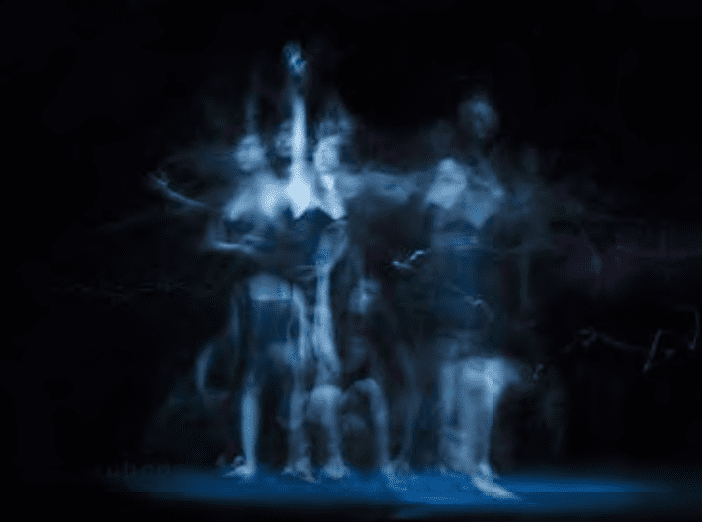

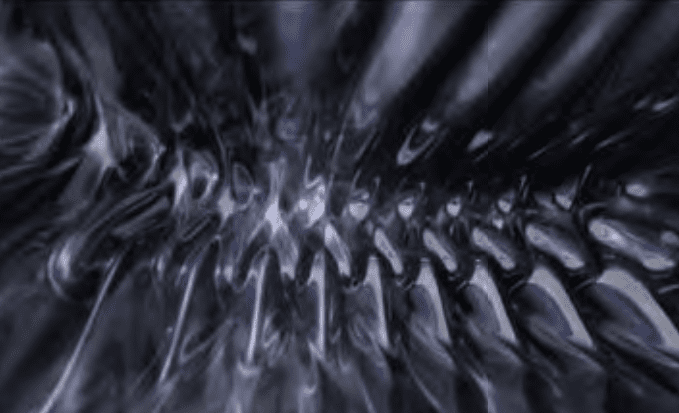

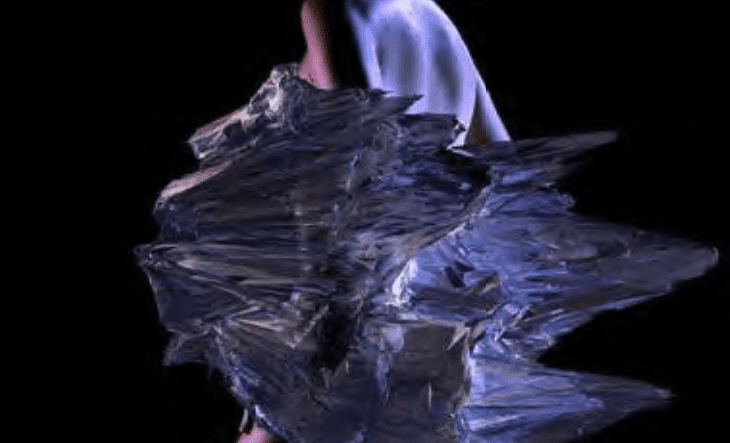

Petresin’s practice, often taking the form of performances (Dissolutio, 2013), immersive experiences and multimedia installations (Iwasi, 2004-11), while touching on the social perspectives of biopolitics and transhumanism (Audiomorph, 2011. Qaniyatu Elima, 2012), lent towards the universal. Artistic practices like embodiment, transformation, manipulation of time, and synaesthesia in syncretic art worked to move beyond the simple and contemporary, crossing the bordered relationships between society, the body and technology. But her relationship with architecture and structure (Structure in Flux, 2010) often took a central place in her work through the study of optics, complex geometry and acoustics, teasing out how we perceive these concepts as guiding structures. Structures which she often portrayed as fluid (Wave_Strings, 2010), generative and subjective. In many ways, reactive and thus alive.

‘Exploring intangible structures: her voice, the contemplation of light, image, movement and the barriers between intimate and public spheres. This format enables her to extend analogue media into immersive experiences of contemporary rituals. She is critically addressing environmental issues, climate change, clean water and free energy, providing reflections on technological and progressive utopias.’ (bio)

On one level, Autonomous Energy Machine is a meditation on fluid dynamics, endless energy sources, the history of science, and an experience of scientific concepts within an emotional and social frame. Housed in a ‘secret lab’ containing blackboards with the scientific history of energy described as a lineage of formulas, the acrylic glass prototypes of fluid energy devices with their pipes and turbines resemble isolated human organs or maps of circulatory systems. The human body being itself characterised by a series of pumps, tubes, filters and energy-producing chemical furnaces, the connection is both internal and external. As much as we should take care of our bodies, we should consider the world along the same lines with its own vital connective organs and systems. In effect, both the world and us are energy systems are connected.

Vesna & Eugen Petrešin, Autonomous Energy Machine, 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, 2025. Photo: Jaka Babnik. MGLC Archive.

The idea of endless, free and clean energy is a utopian ideal which, akin to the perpetual motion machine, has been something pursued by scientists for centuries. Leonardo da Vinci stated in 1494: ‘Oh ye seekers after perpetual motion, how many vain chimeras have you pursued? Go and take your place with the alchemists.’ Controversies regarding whether cold fusion has been achieved have continued since 1989 when the apparently successful Fleischmann–Pons experiment was made public. To the extent that now cold fusion experiments are labelled as being part of a ‘pariah field’, bordering on pseudo-science, meaning that studies are hard to fund, peer-review or publish. Hope, of course, springs eternal.

Artistic visions of a better future, however, are not limited by scientific backing. And surely the vision of a utopian world is a crucial pole star for navigators looking to lead us out of dark waters. Autonomous Energy Machine is thus a reflection of our hope for future solutions to current problems. How those hopes are constructed. How many ideas of the future are drawn from biomorphic fears and dreams framed by our culture’s conceptions of life. Technological advancements are, in that sense, extensions of our conceptions of the body – thematic allegories of growth, increase, expansion and death. An understanding which suggests that looking ahead requires as much inward attention as outward.

‘Men are recognised also by their relationship to water’ – Vesna Petresin (Autonomous Energy Machine, 2025)

Looking at the static energy prototypes, the viewer imbues them with vigour, wishing they would burst into life. Walking into a dark room with a few lonely apparatus spotlights on pedestals would have a static feel if it weren’t for Petresin’s voice echoing from all sides, rising and falling on the edge of intelligibility. Flowing around like the energy absent from the prototypes themselves, they provide the immersive vessel for the viewer to power the machines themselves. In that respect, the work functions to embody the viewer within the scientific utopianism, as the water that powers the turbines, the river of life itself.

For an artist with so much to explore, this was perhaps, given something of a choice, the way that Petresin would have liked to leave – having closed on a particular project and ready for the next adventure. But also leaving a breadcrumb back to her earlier works as a means to understand her creative journey. Pathways back to her immersive work which themselves viewed speculative structures as coming from generative principles multiplied through repetition and often adapting to the viewer’s interactions. It seems glib to speak of a shamanic futurism with regard to her work, and yet traces of ritualism regularly peeked through. Eliciting changes in consciousness, a refactoring of perception, and the construction of receptive fluid worlds, the work lends itself to both esoteric and philosophical readings.

As per writer William S Burrough and sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, Petresin’s work claims that there is never really a static order of things, rather things exist in a state of flux where the individual has a more or less influence within a context that is in turn influencing them. In a word, immersive, but investigatively so. If, as per her work, we are in a constructed personal utopia, what would such a world say about us? In that respect, Petresin fit easily within the theme of the 36th Ljubljana Biennale, the oracle. Oracles purport to tell us our futures, and while the active reality is distinctly in the present, the magic is in presenting us with the connective means to realise our utopias.

Petresin left behind a solid and valuable body of work, many of which dealt with the connective means through which we can use technology as a vehicle for a conscious future-making. And also as a means of feeling the parameters of our imaginations and, by extension, our minds. Something made all the more poignant with her passing. Her particular beliefs regarding an afterlife are unknown to this writer; however, artists live on through their works. Artworks are a summation of an artist’s approach to consciousness and perception, and in the immersive methodology of her work, one feels there is a heightened transmission of the artist where the usual boundaries between viewer and artist are transcended. We become a part of her work, enabled to find our own futures; we join her not to a definite end but forward along the shifting edge of our becoming.

Vesna Petresin 6 May 1971 – 27 May 2025

–

36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts Dedication

6 Jun – 12 October 2025

Her 2021 lecture on Art and Immersion

Images courtesy of Natasa Petresin Bachelez / MGLC Archive

Prof. Dr. Eugen Petrešin, a scientist in the field of fluid mechanics, who has dedicated his career to environmental science and technology, particularly urban hydraulics and water pollution control.

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. LSE Masters Graduate. Arts and Culture writer since 1995 for Future Publishing, Conde Nast, Wig Magazine and Oyster. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.