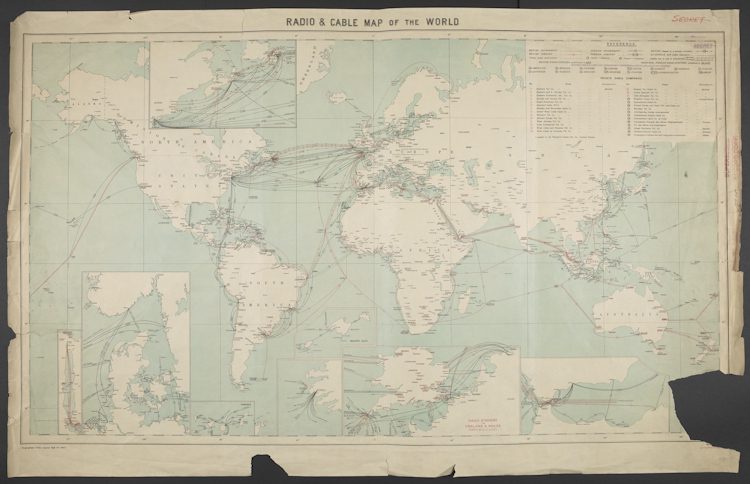

In 2015, Private Eye magazine published a map revealing how more than 100,000 properties were owned by offshore companies. In 2016, the simple transit map shared by Syrian refugees via encrypted messaging showed an escape route from the Turkish border across Europe and into Germany. In 1927, the British government created a map of the cables used for communication worldwide. More than just a cartographical exercise, secret government offices used the map to isolate communication stations and listen in to messages sent by enemy forces above ground and beneath the oceans.

Secret Maps, the latest in the British Library’s series of blockbuster exhibitions, plunders the organisation’s extensive archives and collections to explain how the simple chart can be so much more than a way of showing how to get from A to B. Thus, artefacts used for clandestine operations and activist activities line up alongside documents used in socio-political change and enforcement. The Private Eye, Syrian refugee and international cable maps are part of the exhibition’s final section, entitled Personal Secrets. The show opens, though, with the ‘Imperial Secrets’ section, a room of charts used by Western powers to plot their often nefarious colonialist ambitions over time.

Ahead of the partition of India in 1947, Clement Attlee’s government created a map of the country to interrogate how Great Britain would benefit economically and militarily from creating the nation states of Pakistan and Bangladesh. A map from 1596 illustrates potential routes to be used by Sir Walter Raleigh in his journeys to South America to extract gold from the continent. Māori chief Tuki te Terenui Whare Pirau’s 1793 map is here, too. He used it to expose the difference between the beliefs of his own people and those of the colonialists who were arriving from the West to invade his New Zealand homelands.

This exhibition grapples with an alternative set of realities. Maps can be beautiful pieces of documentation; elaborately decorated and imbued with mystery and conjecture about lands unknown. Secret Maps manages to sidestep the obvious temptation of leaning too far towards this kind of emotive, decorative response. The show’s explanations of how maps can be troublesome and disruptive symbols of dictatorship, power-grabbing and paranoia – as well as manifestations of forced migration and the desperation for escape – are calm and clear.

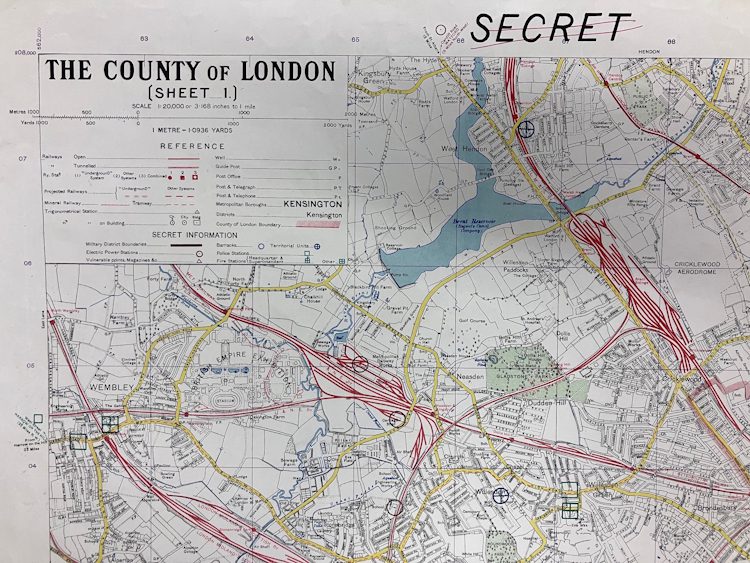

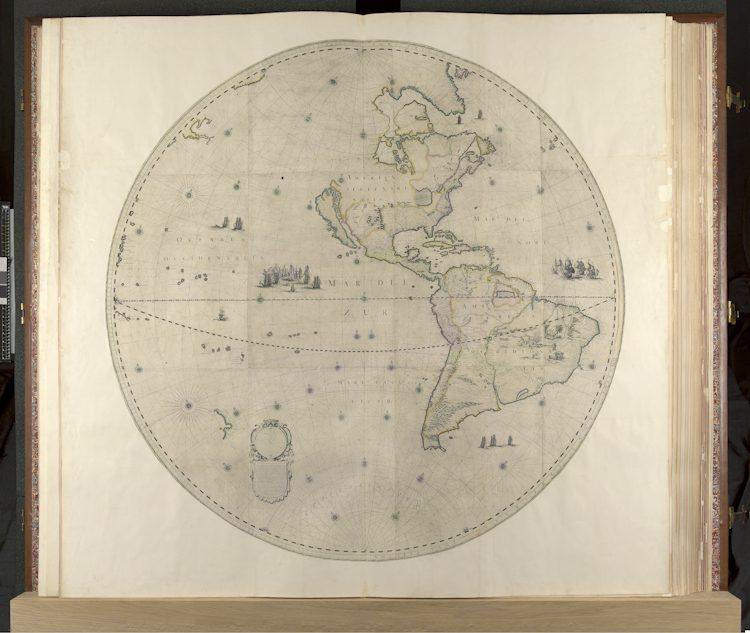

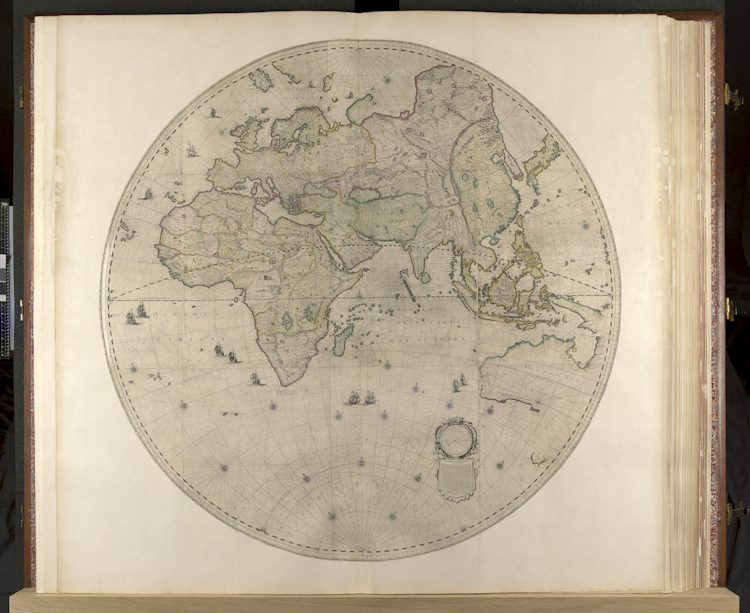

The show’s ‘State Secrets’ section is a further disquisition on how countries’ rulers thirstily attempt to extend their influence and control their positions. During the 1926 General Strike, the British government commissioned a secret Ordnance Survey map to highlight areas where strikers were most likely to riot. One of only two existing copies is on display. Elsewhere, a faded globe and a set of drawings made in the early 1600s by master astronomer and mathematician Willem Blaeu map out the Dutch East India Company’s growing trade monopolies in global territories. Less sinister and more hopeful, an innocent-looking hairbrush hides escape route maps beneath its bristles. The brushes were sent to Allied prisoners held in German camps during the Second World War.

Next, the exhibition’s ‘Secrets in Society’ section is dedicated to social primacies; the important aspects that underpin matters of personal importance. Assembled in the 1970s by members of London’s LGBTQ+ community, the ‘Gay To Z’ is a mapped directory of gay-friendly safe spaces in the city. It is a tender and clever document. Fanned out like a captured butterfly in its glass display case, the sixteenth-century khipu (a series of knotted ropes) is an intriguingly simple device used to record sacred Incan landscapes. Despite being separated by the ages, the common intention – the wish to be allowed to exist without fear – shared by the directory and the khipu is touching.

By contrast, the Google Earth installation near the end of the exhibition feels gauche and shouty. An interactive map of the contemporary world, it is an unashamed model of how data can be harvested on a global scale. Maybe its presence is meant to provide a counterpoint to the exhibition’s overarching notion of secrecy? Either way, the omnipotence of the piece is a glaring reminder of how easily the world moves on. Where once paper documents enabled navigation, technology now provides the tools, logging humanity’s direction of travel with relative impunity along the way.

Secret Maps comes after the British Library’s Unearthed: The Power of Gardening, an exhibition that explored the UK’s relationship with domestic agriculture. Overall, Unearthed felt a bit quaint and unadventurous, like an afternoon spent watching cosy crime repeats in between the chairlift adverts on a linear TV channel. However, the exhibition did include small parts that delighted in gardening’s subversive side, including exhibits explaining how movements like the True Levellers and the Diggers fought against governmental landgrabs. Secret Maps takes that approach further, using the British Library’s access to endless stacks of historical documentation to showcase the radical ideas (both good and bad) behind a map’s nominal function.

Secret Maps 24 October 2025 – 18 January 2026 The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB

Secret Maps at the British Library

Images courtesy of the British Library © The British Library Board