[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]n the last post, I visited Mbare, the oldest black township in Zimbabwe’s capital Harare.

The neighborhood is dominated by high-density, low-income housing, the most visible of which are the long rows of ugly brick and cement apartment buildings known locally as hostels.

Overcrowded, dirty, and dilapidated, from the outside, these hostels look like hell holes, the only refuge for people living on the edge. It’s difficult from the safety of a vehicle driving through the township to comprehend the lives that are lived in these dreary blocks.

From other travels and experiences in poor countries, I knew that even in hardship, there is life. That people smile, cry, love, and die just as in every other place in the world. I wanted to visit, to see and gain a real feeling for the place, rather than sit back and let prejudice craft an experience for me.

Mbare is more than Zimbabwean. It’s a cultural melting pot that has brought together men and women from throughout the region. During the Rhodesian era, the white government used the township as a kind of holding district, a ghetto for working class men who provided the labor for the factories and other industries in the capital, Salisbury. The hostels were built to house men and men only. The showers are unisex; the apartments are small and cramped. They weren’t designed to hold families.

Women weren’t allowed in the townships. It helped keep the male population under control. The apartments weren’t meant to be homes, merely housing. The policy dehumanized an entire population. Labour was merely an input to serve the country’s industrialization.

While wandering through the quiet streets, we met Luso, who agreed to show us around the hostels and introduce us to some of his friends. Luso was a Malawian who had stayed on after the government cleared the slums that had cropped up around the city. Known as in Shona as Murambatsvina, “Operation Clean Up,” or, more literally, “Operation Refuse the Dirt.” In 2005, the government moved bulldozers and heavy equipment into the poorest of the urban areas, ostensibly to clear dangerous informal housing and clean up crime. Many saw it as an attack on opposition supporters, as the MDC drew much of its support from these underserved areas.

Within weeks, the townships had been transformed, at the cost of many peoples’ homes and livelihoods. Some returned to the rural areas. Others left the country, never to return. Areas that used to resemble Kibera in Nairobi or Kayelitsha in Cape Town now look much like they did in the 1950s – just overcrowded, underserved high-density housing reminiscent of American projects or English council estates.

As Luso led us through the property, we came upon some children playing at gymnastics. They had set up a large truck tire at the end of a long stretch of pavement bordering one of the apartment blocks.  With a long run up, they would launch themselves from the concrete, stomp the rubber rim of the tire and use the force to catapult their bodies up and over, performing a full flip before landing on a pile of stacked quilts and blankets.

With a long run up, they would launch themselves from the concrete, stomp the rubber rim of the tire and use the force to catapult their bodies up and over, performing a full flip before landing on a pile of stacked quilts and blankets.

They did it over and over and over, sprinting down the concrete, hitting the tire, and flying through the air. Occasionally they would land on their feet, more often they ended up on their backs or at times with their nose planted in the cushions. The kids were fearless, as only kids can be. They weren’t old enough to remember the bulldozers that destroyed their neighbor’s homes.

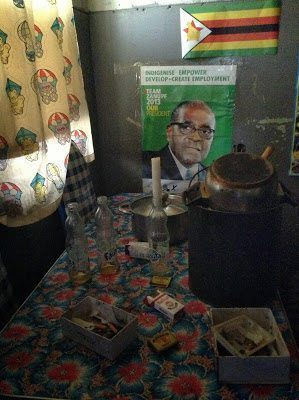

Luso introduced us to his friend Sylvester, a short, powerfully built man who’d filed his front teeth into points. Though young, lack of proper dental care had rotted the points into jagged, brown clumps. He wore a shirt advertising his allegiance to ZANU-PF, but I wasn’t sure, and didn’t want to ask, if he supported the party or merely supported the giving away of free shirts.

The government has a strong hold on Mbare. Campaign posters mark several buildings and trees, but it’s unclear if it’s politics of the heart or of the stomach that affords them such support. A free tee-shirt or hat can go a long way. Giving away food before an election can go even further.

Sylvester led us up two flights of dimly lit, heavily worn stairs. The hostels were built in the 1940s, and the cement stairwells exhibit the smooth, rounded corners of long use by many people. A woman ran a small shop at the entrance to the building. She sold tomatoes, onions, oil and other essentials one commonly needs on short notice. As we reached the second floor, we met Sylvester’s friends, all young men in their twenties and thirties, sitting idle on a Tuesday afternoon.

One could fault them for not working, but the reality of Zimbabwe is an unemployment rate that is catastrophically high, up above 80% in Zimbabwe’s formal sector.  Women often work informally buying or selling goods in many of the townships’ markets, but for the men, who are more used to hard labour or more masculine pursuits, there is little demand for their labor. Sylvester’s friends smoked marijuana and watched the world go by, much like their counterparts in Western project houses.

Women often work informally buying or selling goods in many of the townships’ markets, but for the men, who are more used to hard labour or more masculine pursuits, there is little demand for their labor. Sylvester’s friends smoked marijuana and watched the world go by, much like their counterparts in Western project houses.

Sylvester’s room was small, maybe only fifteen square meters. He shared it with his wife and younger brother. His brother used to live in another building, but had to move in when a kitchen caught fire, smoking out the residents and damaging the building. So it goes. Sylvester owned a television, a bicycle, a radio. He made do off “one day’s work, when it comes. One day here or there.”

What struck me about the hostels was that, even though they looked filthy from the outside, they were actually very clean. There was an obvious pride that the residents held for their homes. The walls held years and years of smoke from candles and cooking fires, the paint was cracked and peeling, but the floors were clean, the toilets, shared between dozens of people, serviceable.

[quote]If there’s one person

there who is staunchly

pro-Mugabe, he or she

dominates the conversation[/quote]

We left the hostels for one of the local shabeens. With no women and little entertainment, many men escaped through alcohol. The Rhodesian government encouraged this, building massive community taverns with shaded courtyards and cheap beer. Though they sell bottles of Castle and Black Label, the shabeens do most of their business in local brews. Oscar and I split a bucket of chibuku, the sorghum beer favored all over the African continent. Eighty cents bought two litres of the thick, sour concoction.

“It’s a meal and a drink!” said Chibwe, a retired civil servant who frequented the bar on a Tuesday afternoon. “When you want a meal, but don’t have much money, you drink this. And you get drunk too!”

Despite it being 1:30 in the afternoon on a Tuesday, there were still a handful of men at the bar, mostly old age pensioners or middle aged security guards waiting to start the night shift. The old men dressed impeccably, pressed shirts and stylish hats harking back to an earlier time. When you have so little, you take pride in your appearance. It’s one of the few markers that you have any control over.

These guys weren’t alcoholics, but they did drink. The shabeen on a weekday afternoon is as much a social space as it is a drinking place. The leafy garden keeps the worst of the spring heat at bay, and if you’re lucky, someone will come along to buy you a drink.

“I can’t stand the chibuku, it’s for me, Blue Diamond.” Phenias was a war veteran, or so he claimed. When I pressed him further, I learned that he’d joined the army in 1980. If he were an independence fighter, he hadn’t fought for very long. I slipped him a dollar, and the fifty-five year old ambled off, returning several minutes later with a small plastic flask. Its blue lid and crystal clear contents belied a poisonously powerful local vodka. He mixed it with equal parts with water. “You have to dilute it,” he said, giving me a drink. Even diluted, it tasted like a mix of rubbing alcohol, coconut, pineapple, and benzene. I nearly choked.

I’d be sticking to the chibuku.

We spent the afternoon drinking and chatting. I tried to raise some political questions, but whenever I did, Phenias took the opportunity to answer for the group. It’s a common problem I’ve encountered in Zimbabwe. If there’s one person there who is staunchly pro-Mugabe, he or she dominates the conversation, cowing others into quiet agreement.

I wanted to hear other voices, other opinions, but Phenias dominated the conversation. I quickly had little to say to him. By three o’clock, the worst of the heat had passed, and we left Mbare.

Driving past the hostels, the shabeens, the Mai Musodzi Community Center, and the Pioneer Cemetery, I could reflect a bit on what I’d seen. Certainly, it was nothing out of the ordinary, but the boring of the everyday brought life to the community. Before I visited, I might stare blankly out the window of a bus passing through the township. I might see a certain community hall or a dilapidated hostel and think little more of it. Now that I know a bit about the township’s history and its people, I can’t unknow what I’ve learned.

These people, these places, they’re real to me now, they matter. In a place like Mbare, where even Zimbabweans fear to go, this recognition is what matters. Not the recognition of a white man, but just the simple acknowledgment that they inhabit one planet, the same planet as I. It’s a powerful connection for a community that has long been overlooked.

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.

How did you manage to get such nice pictures of Mbare. The truth is that the place is a terribly poor, dirty and dangerous place. I’m surprised you were able to even take any pictures without someone wanting money or to take you to the police… Well done 😉

I’ve found that there’s nothing more or less sinister about a place because of its poverty. I had a friend who has been trying to set up township tours in Mbare. He is full of information and has many contacts, but it’s still in the early stages. It’s a fascinating place. I only wish I had more time to explore!