[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap] new cast of characters has taken centre stage in Tom de Freston’s latest paintings on show at Breese Little in London.

Orpheus and the Minotaur takes its title from a mythological hero and monster and brings to mind the dark Underworld where Orpheus descends in search of his bride Eurydice, and the Labyrinth designed as the Minotaur’s prison. Far from offering straightforward references to classical mythology though, de Freston meshes these with visual motifs from the canon of art history and poetry, creating uncanny and complex but rewarding works. Indeed, this series of works were born from a cross-arts project about Orpheus and Eurydice with poet Kiran Millwood Hargrave and theatre director Max Barton.

Tom de Freston, ‘Bath’, 2014, oil on canvas, 200 x 170 cm

Tom de Freston, ‘Bath’, 2014, oil on canvas, 200 x 170 cm

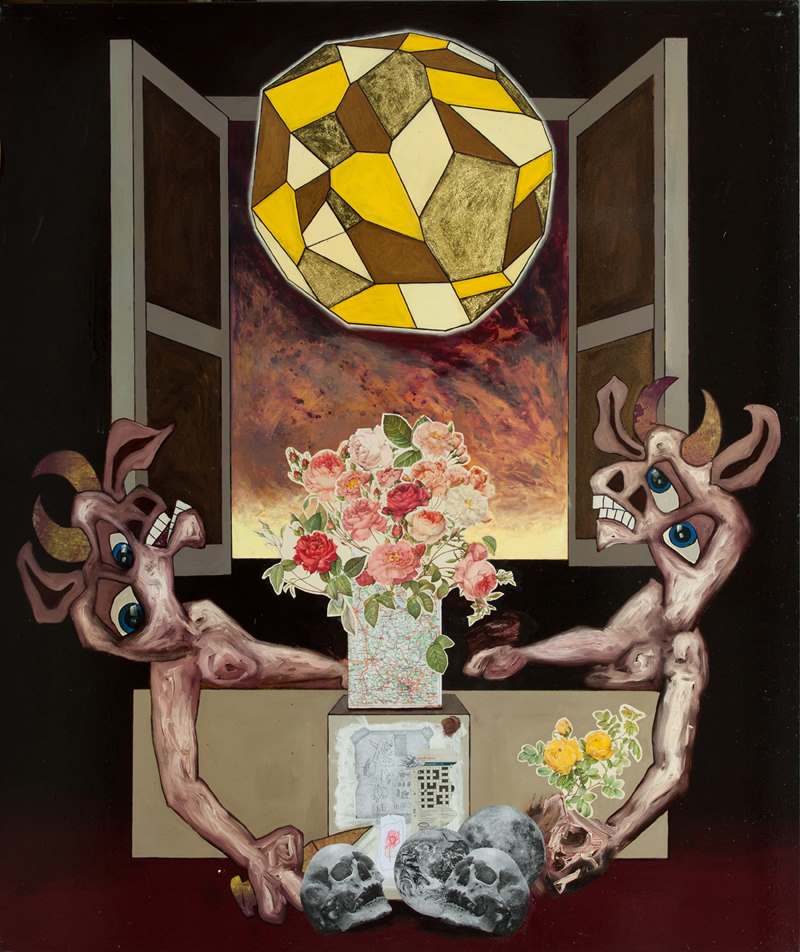

‘Bath’ could hardly be a more mundane title for such a painting. Two bull-headed figures sit in a bath face-to-face, nearly mirroring each other. Almost mirrored images or ‘doubles’ (including dolls or automata) were identified by Freud as provoking an uncanny feeling, or an uncomfortable sense of déjà vu which instinctively makes us want to take a second glance to make sense of what seems irrational. Perhaps this unsettling feeling also has something to do with the memento mori-like skulls or the familiarity of the figure’s pose which recalls Jacques-Louis David’s painting of Marat dying in his bath, a limp arm hanging down the side.

The setting amplifies the unease: an undefined space with a window opening onto a fiery otherworldly sky and the absurd irruption of a bourgeois bouquet of roses, probably salvaged from a horticultural volume, collaged in the middle of the painting.[quote]His work has little to do with the

emphatic and aggrandising tradition of

history painting and instead reflects on

the stories of less well-known characters

and people[/quote]

The introduction of collage is a new development in de Freston’s work. Arguably the collage is an extension of his practice of, in his own words, ‘scavenging’ motifs from Western art history from Masaccio to Bacon and Titian to Picasso and transforming them for his own purposes. But the effect produced by the collage is certainly different. In placing naturalistic representations of skulls, a bouquet and incorporating ‘ready-made’ graphic elements such as a map and a crossword grid over the painted surface, de Freston, like the Cubists with papiers-collés, plays with the Renaissance artistic tradition of illusionistic space.

Standing in front of his work you realise that the illusionistic skull placed over the painted hand of one of the figures and next to a crossword puzzle is flat and that there is no actual depth even in the open window. In other words, de Freston is now drawing on the history of art for techniques as well as motifs. Although this might sound like a formalist reading of Cubism, de Freston’s new unifying shiny gloss and glitter across the surface of all but one of the paintings on show also suggests that he is drawing attention to the surface of the painting, to remind the viewer that these are all in fact illusions.

In another mise en scène, ‘Elegy for Elsje’, a forlorn figure lies in a boat resting on the floorboards of a dark cellar-like space. It could be a stage with props – the boat, Van Gogh’s sunflowers which now look like eyeballs – and actors, all lit by a dramatic shaft of light. But the clue is in the boat’s name ‘Elsje’ and then in the sailor’s face which I eventually recognise as Rembrandt’s and the collaged reproductions of the Dutch master’s drawings of a dead girl on a gibbet.

Elsje Christiaens was a young Dutch maid executed in 1664 for the murder of her landlady who had threatened her. We are still firmly in the underworld, as she, like Eurydice (although for different reasons) died very young, but in a perverse way is now remembered precisely because of her unfortunate story and Rembrandt’s drawing. No doubt Eurydice would have been less famous had she not stepped on the fatal snake and lived a happy nymph’s life.

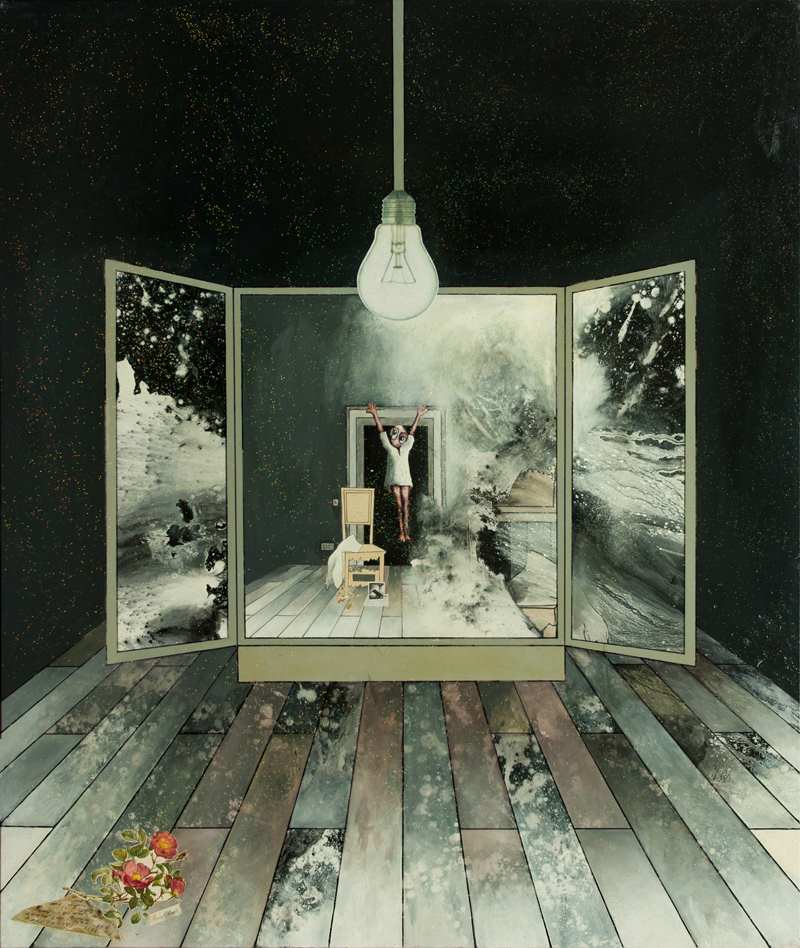

One of the paintings I’m most drawn to appears to stand slightly apart from the other works. There is no sign of a Minotaur and it is quite pared down, with a triptych standing on floorboards surrounded by darkness except for a collaged light bulb hanging down the centre. The central panel of the triptych represents a figure hanging from a doorframe drawn from one of Francesca Woodman’s haunting photographs taken in the late 1970s. A small reproduction of one of her other photographs is collaged as if propped against the chair as a further visual clue to her work.

Tom De Freston, ‘Francesca Woodman II’, 2014, oil on canvas, 200 x 170 cm

In the bottom left of the painting, a small scrap of collaged paper lies on the floor and if you look closely (and turn your head upside down) you can make out a 19th century poem by Emily Dickinson. It rings a tragic note juxtaposed to Francesca Woodman’s work which evokes her personal story of depression and finally suicide in her early 20s:

In this short Life

That only lasts an hour

How much-how little-is

Within our power.

But then you might notice that what seemed like a mise en abyme, with the triptych within the painting, is perhaps rather a painting of a mirror reflecting the room’s floorboards, meaning that you, the viewer, are reflected and that you are the figure hanging on the doorframe. This is all the more disturbing if you notice this figure’s similarity with the crucified Minotaur in the painting next to it on gallery’s wall. In effect, this makes you the anguished looking Minotaur in other paintings too.

By extension these paintings are about something more than the series of unfortunate young women from antiquity to the 20th century: Eurydice, Elsje Christiaens and Francesca Woodman, leaving behind them a myth, a couple of drawings or a body of photographs. Perhaps this is what de Freston means by saying he is a ‘contemporary history painter’. His work has little to do with the emphatic and aggrandising tradition of history painting and instead reflects on the stories of less well-known characters and people (unsurprisingly these are women) which, despite their relative obscurity, can speak to the viewer

This exhibition marks half a decade of prolific work. Amongst many projects, de Freston has completed a commission for the chapel of Christ’s College, Cambridge; has made a series of paintings for the British Shakespeare Association in response to Shakespeare plays; and has collaborated extensively with theatre directors and poets – his latest book project The Charnel House a ‘poetic graphic novel’ is about to be launched. He has developed in leaps and bounds – and shows no signs of stopping.

At Breese Little Gallery, 30b Great Sutton Street, London. Until December 13.

[button link=”http://www.breeselittle.com/past-tom-de-freston-minota/4587062038″ newwindow=”yes”] Orpheus and The Minotaur : Details[/button]