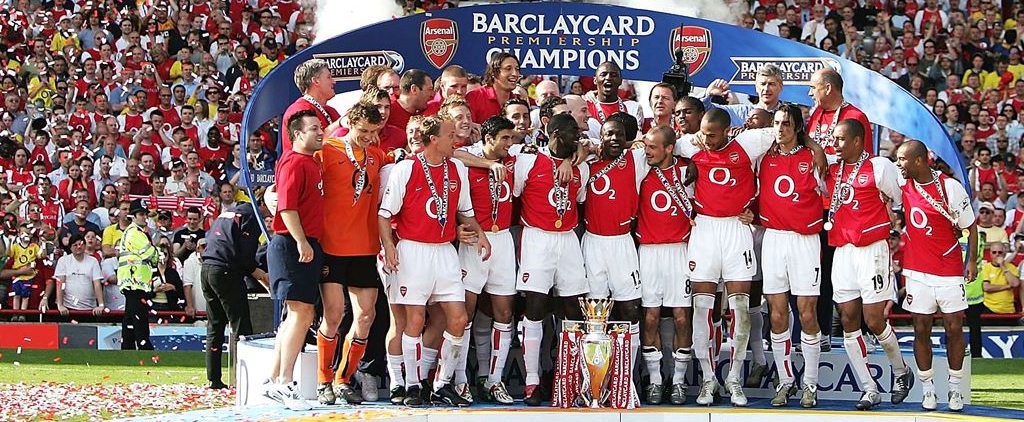

Arsenal Invincibles 2003-4, English Premier League

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]I[/dropcap]s it at all possible that football, at its highest level, is an art form – a game of genius?

The ponies run, the girls are young

The odds are there to beat

You win a while and then it’s done

Your little winning streak

And summoned now to deal

With your invincible defeat

You live your life as if it’s real

A thousand kisses deep

(Cohen, 2001)

Dear Arsène Wenger,

You shall be sorely missed at Arsenal. What you brought to the club, and to football in the English Premier league more generally, was a conception of football as an art. The Beautiful game.

Thank you.

Of course, it is possible to wonder whether football could be an art.

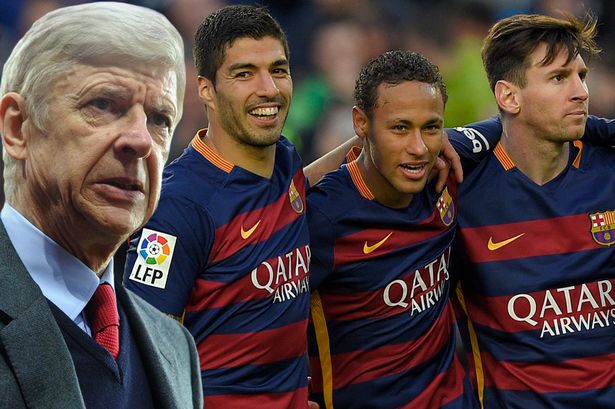

However, a slightly more modest conception of what football might be, is contained in Wenger’s interview after losing 3-1 to Barcelona in the UEFA Champions League.

Barney Ronay’s piece in The Guardian contains an edited video-clip of the post-match interview with Wenger, in which the Arsenal manager starts by saying that football played the way Barcelona play is an art. Later he modifies this by saying ‘they have two or three players who can transform normal life into art,’ and that it’s ‘a pleasure to watch.’

Arsenal are out of the Champions League, beaten 3-1 on the night, but Arsène Wenger was magnanimous in defeat, describing Barcelona’s attacking football as art and their extraordinary forward line of Lionel Messi, Luis Suárez and Neymar as players who “transform normal life”. (Ronay, 2016)

Football is, of course, the beautiful game. However, many things are beautiful that remain ‘normal life’ – the experience of a sunset or a beautiful forest or a seascape; crocuses just before spring. Whilst these are undoubtedly beautiful scenes, events or objects, they remain natural and therefore normal. No-one is responsible for them and so no-one can take credit for them, any more than anyone can be blamed for horrible disease or catastrophe.

Beautiful nature is not the result of agency.

So, what about football, the beautiful game? And why does Wenger pick out three individual Barcelona players?

Real fine art, claims Kant, is the result of genius. The genius himself (or herself – a possibility Kant overlooks) does not know how the work achieves its special quality. The work is original. It is not the result of any rule. The work of genius itself provides the rule for others (non-geniuses) to follow.

Other artists, those not blessed with genius, are able to follow these rules but in so doing they will never achieve the status of genius. Their products, like those of craftsmen, might well be enjoyed by many, but they are nevertheless short of the mark of genius. Poor old Red Star Paris is such a team.

Red Star Paris(in green) v Creteil in French 3rd tier, April 2018

Kant thinks that no scientist can achieve genius as the work of the scientist builds upon the rules that others have discovered. Science, on Kant’s view does not require originality. It is simply a different kind of human endeavour. Only art requires the degree of originality that is the mark of genius.

Kant also warns, ‘Nonsense, too, can be original.’

In the scheme of the fine arts, Kant ranks poetry as the highest. Percy Bysshe Shelley, following Kant writes that ‘poetry creates anew the universe’. (Shelley, 1971)

In this, we might recognise the romantic idea of fine art bequeathed to us by Kant. Shelley resonates nicely with Wenger’s comment that the three Barcelona players can ‘transform normal life into art’.

Football is not, as yet, recognised within the system of the fine arts. Could it possibly become an art? Could it transform itself into a fine art?

There are good reasons to think not; and Wenger gives at least one in the interview above. He says that in recognising football as an art, it gives pleasure and adds that, ‘of course for me it’s suffering’. Now football thrives on its tribal nature. Not only players, but fans as well belong to a team.

Whilst you might enjoy a good game, there is a terrible sense of loss at your team’s defeat. And that defeat is not something aimed at in the game. Judging a side’s performance is not like judging a work of art. Works of art, unlike football matches, are, relatively speaking, permanent.

We want to return to buildings that we love. We want to return to the concert hall to hear the symphony we love; to the art gallery to look again upon a masterpiece; we want to read again the novel we know already, the film we have seen already, and so on.

A football match, however, is something that is wrapped up in its outcome. The game cannot be returned to in the same way as a work of art can be enjoyed again.

Moreover, Wenger provides the status of artist to only three of the Barcelona side. What of the others? Presumably they are journeymen or craftsmen. What then do we make of their work within the match we watch?

Nevertheless, Wenger is onto something. The three players, Messi, Suarez and Neymar (the last, now at Paris Saint Germain) are, quite possibly geniuses. No-one knows where they get their abilities and, in conformity with Kant’s notion of genius, the abilities they have cannot be coached.

Arsène Wenger, Louis Suarez, Neymar, and Lionel Messi

Another possibility is offered by Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche writes of intoxication in his book, The Birth of Tragedy.

There he identifies two impulses alive in the creation of art, the first Apollonian, the second Dionysian. Apollo and Dionysus were the sons of Zeus.

Apollo represents all that is rational, prudent and pure. Dionysus, god of wine and dance, represents irrationality and chaos. It has been claimed that Kant is concerned only with the Apollonian impulse. The great works that we see in galleries, in concert halls or at the ballet, belong to the detached attitude of the spectator at a distance from the art to which she attends.

The white cube is the space to look at art; whilst, conversely, it is in the wine wetted streets the fiesta unfolds. Perhaps, we might think of football as a Dionysian art, like the art of the fiesta in Spain. Zeus alone knows how many pints of lager get drunk in the pubs around The Emirates on Arsenal home games.

But neither the fiesta nor the match is a thing we can call a work of art. For the Dionysian impulse alone, whilst undeniably aesthetic, results in nothing (‘no thing’) created. Art, we want to think is, at least in part, crafted. And what is crafted belongs to a medium in art. In neither football nor in the fiesta is there anything that could properly count as a medium – for a medium is what provides art with its permanence.

Let us enjoy football as if it were an art, whilst realising that it is not.

Let us regard it as an aesthetic endeavour, one which Arsène Wenger has helped to develop in his career at Arsenal Football Club.

If football were an art, we would have no need to follow teams that do not have genius within their ranks. We should seek out only the teams that have such players. That, however, would be the end of football.

Supporters cleave to their sides and live as if it really counts (what happens on the pitch). It doesn’t. At least, it doesn’t matter in the real world. It might matter in the world of the supporter’s imagination, but, unlike art, there is no connection between the imagined world of football and the world as transfigured in art.

Football does not create the world (let alone the universe) anew. As the painter, Georges Braque once remarked, ‘Reality only reveals itself when it is illuminated by a ray of poetry.’ For those of us, stuck forever watching and hoping: we live our lives, as if it’s real, a thousand kisses deep.

Mr Wenger has left the building.

References:

Cohen, 2001, Leonard Cohen, ‘A Thousand Kisses Deep,’ Ten New Songs

Ronay 2016, Barney Ronay at the Camp Nou, @barneyronay, Guardian Online Wed 16 Mar 23.31 GMT. Accessed on 12th May 2018 at: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2016/mar/16/arsenal-arsene-wenger-barcelona-art-champions-league-defeat

Shelley, 1971, Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘A Defence of Poetry’, 498-513, at p. 512, in Hazard Adams, ed., Critical Theory Since Plato (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971).

Edward Winters presently lives in Paris, where he is writing a book on everyday aesthetics.

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.