[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t is strange to think that in our own time we are convinced that ‘authenticity’ is a greater problem than for the creatives of the past. In this series of articles Natalie Andrews explores why this is and if there is some validity to the concern. Unpacking the seminal 1983 article by Hal Foster and attempting to challenge this and reassert a critical perspective on a seemingly forgone conclusion; that being we are all phoney, fake and fatuous. Read part 1 below.

Authenticity and The Expressive Fallacy

The article The Expressive Fallacy, appeared in 1983 in Art in America, here the art critic Hal Foster explores expressionism and its underpinning (as he sees it) paradox; a stance which trades on a supposed special relationship with emotion, the self and authenticity, as false. The ‘fallacy’ of the title further asserts that expressive artists simply apply a contrived language which is effectively an empty gesture as it only pretends to be truly expressive and is instead like any other form of representation; a socially and culturally mediated set of conventions.

To offer a basis for comparison and to highlight Fosters pessimism we can consider Charles Baudelaire, On the Heroism of Modern Life, (1846), which similarly attacks what is defunct for the critic. From the Salon of 1846 reflecting 137 years before Foster on what he saw as the affliction of his own time, Baudelaire does chime with some of Fosters statements indicating a kind of cyclical nature to renewal or change in art practice.

Dr. Harold “Hal” Foster in Princeton, NJ, 2004

On the Heroism of Modern Life

Baudelaire is critical but far more balanced in his approach, he credits the value of each style and sees these as being abused by ‘lazy’ artists. Looking at the established traditions of his time and the new emerging styles which would anticipate expressive techniques [1]. Baudelaire identifies a lethargic tendency which sees artists repeating forms/styles because it suits them to do so in relation to a stable living and in the pragmatism of exerting the least amount of effort.

‘This dogma of the studios, which has gained currency among the public, is a poor excuse of the artists. For they had a vested interest in ceaselessly depicting the past; it is an easier task, and one that could be turned to good account by the lazy,’ (Baudelaire, C. 1846)

He is referring here to the ‘Salon’ style which developing from earlier more vital artists [2] has become stale and ripe for change; he does however recognise the value of the original style and credits its achievements, ‘idealisation of ancient life – a robust and martial form of life, a state of readiness on the part of each individual, which gave him a habit of gravity in his movements and of majesty, or violence, in his attitudes?’ (Baudelaire, C. 1846).

Edouard Manet’s Charles Baudelaire Portrait Etching

Baudelaire is clear throughout that there are modern values which should be included into any practice and that modern life has an ‘epic’ element, ‘Before trying to distinguish the epic side of modern life, and before bringing examples to prove that our age is no less fertile in sublime themes than past ages,’ (Baudelaire, C. 1846).

Do We Have A Claim to Authenticity?

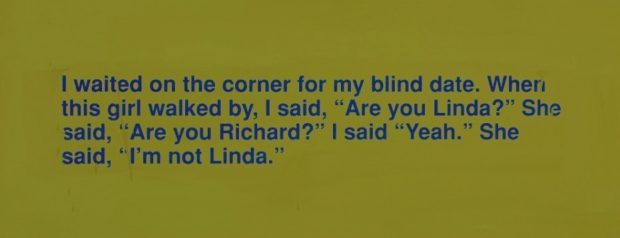

This may be paralleled to Fosters’ advocacy of Cindy Sherman or Richard Prince and their application of doubt and irony; however, Baudelaire’s positivity is lacking in Foster’s theory where the present is seen as a place where only detachment and irony can be asserted; for Baudelaire the subject and the artist are granted more agency, ‘The particular element in each manifestation comes from the emotions: and just as we have our own particular emotions, so we have our own beauty,’ (Baudelaire, C. 1846).

‘I’m Not Linda’ by Richard Prince.

Baudelaire’s modernity is one where the continuation of classical techniques, the antonym of expressionism’s fast and loose approach, is seen as stale or dead, (the opposite for Foster) he also attacks the culprits of this dead style for their pretentiousness as we shall see Foster do,

‘…although the time is past when every little artist dressed up as a grand panjandrum and smoked pipes as long as duck-rifles, nevertheless the studios and the world at large are still full of people who would like to poeticise Antony with a Greek cloak and a parti-coloured vesture,’ (Baudelaire, C. 1846).

As aforementioned though he is quick to praise what was a vital approach, ‘But all the same, has not this much-abused garb its own beauty and its native charm? …political beauty, which is an expression of universal equality…an expression of the public soul,’ (Baudelaire, C. 1846). What we will see is that Baudelaire appears less problematic because he is not putting subjectivity itself, the author in authorial intent on trial as Foster does.

Detachment or be Damned!

Baudelaire asserts that bad artists apply clichés on purpose; we will see that Foster feels bad artists (mainly painters) are fools who are unrealistically attached to a myth of a true self. There are many detailed arguments across many disciplines which debate ‘free will’ and it is not the intention of this essay to settle that matter or to unpack it; only to assert that Foster’s argument is built on an assumption that the de-centred subject is proof of an essentially inauthentic self, an idea which itself is heavily reliant for its validity on deconstruction.

Baudelaire’s optimism is grounded in a belief in renewal, he stands at a point anticipating modernism where Foster writing in the 1980’s is firmly in the postmodern era where he sees only the communication of irony, in-authenticity and detachment as credible motivations for work; and where he cannot imagine the renewal of expressionism or the application of its vocabulary.

The article has important consequences as it testifies to an illegitimate status for artists using expressionism unless they deploy this ironically. It champions, through some of its examples, a detached and ironic approach to art making; reflected in the critical thrust of Foster himself. A close reading of Foster’s argument is necessary to fully grasp what’s at stake and to identify what the consequences are for the notion of authenticity in general.

Part 2 available on 12th September.

Notes

[1] Manet was a close friend of Baudelaire and a hero to the impressionists who would influence Van Gogh one of the ‘fathers of expressionism’ see (Schama, S. 2006).

[2] Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) is an example of a great painter of Neoclassicism. Examples of his memorable works include the, The Death of Socrates (1787) and The Death of Marat (1793) These works portrayed dramatic political themes which expressed David’s political convictions. By the time of the 1846 Salon this style had become stale and passé lacking the dynamism of its high period.

Natalie Andrews is an artist working with a range of mediums, she has shown her work at the Hoxton Arches in London and is currently working on a number of 3d works alongside painting exploring the links between painting and sculpture;

“I am interested in the way that we relate to one another and with space, how the environments we inhabit structure and dictate these relationships and create both opportunities for emancipation but also the deep alienation and separateness.”