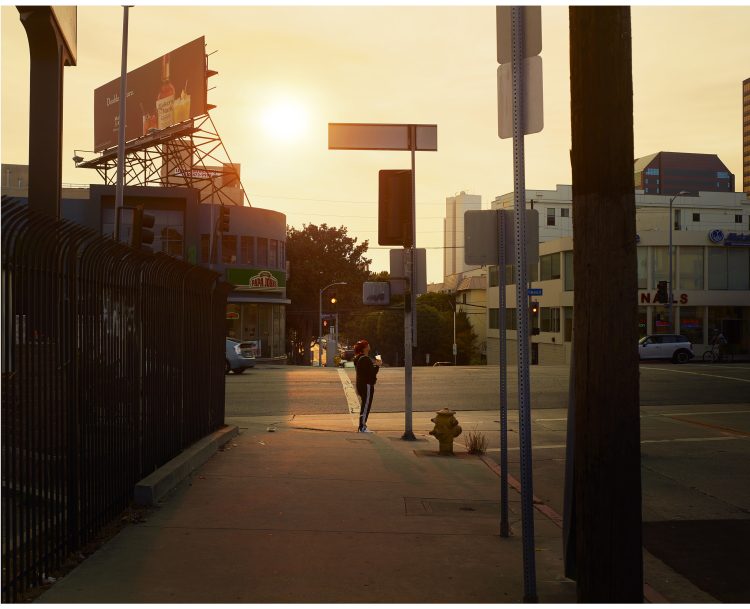

Figures captured at the moment light changes from dawn to day, from Red to Green, from movement to pause. The calm and resonance in Oli Kellett ’s work seems to coil itself around the idea of time.

Stretched and elastic with our attention in Kellett’s work, time is an unseen force, a context that permeates the viewer and the work alike. Into this river, the subjects of Kellett’s photographs might be caught in a solitary moment but they don’t feel alone. Time and light are shown to have almost conscious qualities, as though they chose this moment to stop and join the people in an illuminated moment.

Capturing the right ‘moment’ is of course the primary activity in photography. Any shot holds dynamic elements in a static frame but a good one reveals their connections in aesthetic ways that creates a whole. With Cross Road Blues Kellett proved that he’s got the eye and the aptitude to achieve great shots so his recent decision to follow a thread he found in his artistic practice from his renown to start drawing is odd.

What did he find? And where will it take him?

Now based in Hasting Kellett graduated from Central St. Martins in 2005 and travelling to America used his large format camera, to shoot the everyday as evidence of the sublime through patience, light and chance. Culminating in the now complete Cross Road Blues series he has been recognised at the 2018 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, where he was awarded the Rose Award for Photography and the Arts Club Award. Subsequently, he was awarded the Royal Photographic Society International Photography Exhibition 161 Bronze Prize and, in 2021, he was awarded Aesthetica Art Prize and is looking to exhibit his latest series of Soap drawings in 2022. Back in 2021 Trebuchet interviewed Kellett for our issue on Artistic Process to understand where lessons in time and light learnt from photography can lead.

Oli Kellett: “Crossroad Blues started in 2016. I went over to America with the idea that I wanted to shoot something around the election. So it was in November 2016. I was staying on Hope Street in downtown LA and I thought this is a good start. The reason why I remember, is because there was that famous Shepard Fairey Obama poster, which had the word hope on it, and I thought oh, that’s a nice connection. I thought maybe I could do something around Hope street, walking up and down, constraining my options by just focusing on that one street.

I was there for 10 days and initially I just wanted it to be a series of six to eight pictures. It seemed to work out fine but there were one or two pictures from that series of people waiting at crossroads which made me stop and think. At that point it wasn’t about crossroads at all, it was just the sense that I should build on this the positive outcome of those two pictures. Even though the idea of doing something political didn’t work out, there was something there.

Later I had the chance to go back again and this time I went to a different city. It might have been Miami and again I was walking around but I had more of an idea of what I wanted to make. A sort of American road trip except I wasn’t going to travel anywhere by car so it was an anti road trip.

So, that was it. At that point I was also shooting much, much wider types of subject in other works which perhaps came through. A combination of landscapes and perhaps close ups and I was taking a lot of portraits of people as well. I just wanted to carry on building on those earlier shots. I made more consumer trips and around the sixth trip to different cities I just realised that the Crossroads were featuring very heavily and I thought there’s something in this. Perhaps the reason why I was fixed on Crossroads to begin with, was seeing America at this crossroads. So almost touching on where I was at the start and the idea of Crossroads as a country. I liked the idea of America selling its soul. Then over time, it became much more about people, and a metaphor for the decisions and directions you take in life. So after about six trips, it refined, it became solely about people waiting at crossroads. In the end I went 12-13 times. I usually get one picture for each trip. Each trip is only about 10 days. I have a family and responsibilities for being a parent.

In hindsight, it took a long time, funnily enough, to get to that famous saying ‘oh, he’s at a crossroads in his life’. That never came into my mind for almost a couple of years. It’s too obvious. I suddenly realised, oh that’s what it’s about. It’s about people at crossroads. And that, ideally, they’re looking for something.

There’s a lot of people looking up in the pictures, and that questioning and looking for something, a higher purpose perhaps. I come back to this idea of enlightenment quite a lot. That was the process basically it evolved quite organically from the start without me knowing what I wanted to do. It slowly appeared over time.

The work came to an end, or rather because of the pandemic it was forced to end, with the final picture in Rio. It’s of a man pointing directly up at the sky, and his partner to the left is looking up at where he’s pointing. I knew, as soon as I took that picture, that that was going to be the end of the project, because it cemented all of the previous work. That picture concluded these ideas that I’d been having about–I don’t want to say the word spirituality because that’s wrong–but bigger ideas. Let’s just say that. I’d grown a lot in the four years of the project and that picture was important. The man pointing up, it captured something and I can’t even work around that idea now.

It seems you found the topic of ‘crossroads’ within the work, do you think the overarching theme has muted each photo’s individual impact?

I’m not sure. It looks like I set out that way from the start. But it was really brought home because when someone else pointed it out to me I bitter about it, you might say, I was almost offended. But that doesn’t mean it’s not worthwhile. It definitely raised a few questions at that point.

Importantly it was the idea of silence that I mainly get from the photos. I truly believe we could do with more silence. I’m just about to read the John Cage book, his autobiography, on silence. I’ve been thinking an awful lot about his piece, four minutes and 33 seconds recently and how you need silence in order to make decisions. All that tied together neatly with those pictures of decisions laying themselves out in front of you, or options or pathways. And having that moment of silence to appreciate the idea of direction. In that way the images are meant to look quiet and contemplative. Although I feel that word is sometimes overused a bit, it’s too noisy in a way, when it should mean a quiet moment.

How did you get that vantage point?

There’s a lot of overpasses at crossroads in America, as well as multi-storey car parks. Many of the pictures are from the first floor of one of those. I generally don’t go into buildings because then I have to photograph through windows and people will interrupt. Plus it’s hard to get into buildings.

Car parks are always good. I’ve been thrown out of a few of them. But if you just walk in confidently, you might say your car’s parked there, and then set up. It’s very rare that people care. In fact, there’s one on Van Buren street in Phoenix (Arizona). I’d been there for nine days, and I hadn’t taken a single picture that I was happy with. Then I saw this multi story car park so I spent all afternoon there waiting for the sun, waiting for the light to get right. It’s one of my favourite pictures. I just captured that chap in that red t-shirt and that’s it. You can go on Google Maps or take a screen grab for Google Maps and pinpoint with an arrow where I’ve taken the picture. Some people are generally quite interested in that.

From a technical point of view is it advantageous to be higher because the backgrounds flatten a bit. So instead of being head height, where you’ve got to the horizon, to make the person stand out against, if you’re higher, there’s a good chance they’re gonna stand out against the road, and it’s all about the people, they have to stand out. And that’s why I try to get some height. A lot of the pictures are taken in the very early morning, sometimes late at night, but generally early in the morning seems to work better.

Thinking about my process. It generally starts with me spending a couple of days walking around and thinking where the light will be. Once that’s okay I’ll take the camera with me. There’s generally only two or three places where I can get some height and where the sun’s going to be in the right place. I look for a quiet enough corner that people are going to have to wait. Another interesting thing is that people in America stop at lights. We don’t do that here in London, do we? If there’s a space, you can just walk through them. But in America, the intersections are quite enormous. Jaywalking, it’s a big deal there. You’re not allowed to do it. So that’s why people generally stand still and have that few seconds. The sunlight is important because, going back to that word heightened, I was always quite interested in how in art history the sunlight references the annunciation. There’s light coming through like the dawn of something more powerful. That always appealed to me. It’s not always possible to get and I don’t think the pictures work if the perfect early morning light isn’t there.

Some pictures are taken as early as five or 530 in the morning, right? So you’re capturing people at a quiet time of the day. In those scenarios gestures become very important. I find the gestures of the people inspiring and referential in a way. The chap pointing up at the end that just that was the Death of Socrates that Jacques Louis David painted (1787), also the idea of pointing up is in St. John the Baptist by Leonardo Da Vinci. The pointing up reference was so important and when I saw how it turned out I was ‘No way’ And that was what so it was one of those real moments of Oh, please let me have caught this picture.

Do you auto-shoot a lot of shots to get the right one?

No, no, it’s all manual. So it’s click, then click to reset the lens. It’s an old fashioned lens. On the front of it I have to caulk the shutter and then with the cable release take another one. So there’s a few seconds between each picture. It’s not like I’m on sport mode on an SLR. I use a large architectural camera which is quite slow. Which is good. Well, it has the same camera movements as a traditional large format camera, but it’s got digital back on it. So it looks from the front like an old fashioned camera but from the back it’s not, it’s modern. It’s the best of both worlds. Though it’s quite heavy which is also bad. But it’s not as cumbersome as carrying a proper, old fashioned large format camera.

Does the shot reveal itself to you in any other ways as you’re working in processing them?

There’s usually a feeling that you know that you’ve got a good picture there and then. And then it’s a case of going back and looking at them and looking for that picture or that person that you think something certainly worked in that picture. A lot of the time, we’re not sure what it is that works. Sometimes, it’s definitely a posture that people are holding. I don’t want any phones or anything in it like that, they have to be looking psychologically removed from the physical space they’re in, that’s quite important. And anything that just distracts from that, a phone for instance, makes it so I’m instantly not interested. And that idea of staring out almost glazing over is what I’m after. So going back and looking at them, you generally know if that’s what happened in real time. After that, I process them in Photoshop. I might remove a car that’s in the wrong place but generally, it’s generally all in camera. I’m not a purist in that sense, I don’t have a problem removing a car, or something if it detracts. The colours might be slightly pushed as well. Basically, I do enough to get the picture to a point where it works.

How do you know when your photograph is a completed work? Is there a point where it speaks to you?

It’s interesting you say that, because I’ve always wanted to be a painter. I always…

Continued next week…

Read more in Trebuchet 11: Process

Featuring: Samuel Andreyev / Ed Atkins/ Nairy Baghramian / Phyllida Barlow / Peter Van Dyck / Oli Kellett / Tae Kim / Chris Levine / Gisela McDaniel / Paul Sietsema / Jeff Muhs

Oli Kellett is represented by HackelBury Gallery.

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle