[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]O[/dropcap]ver a bottle of craft ale and some Taste the Difference pulled pork, your forty-something friends confess that, since having kids, they just don’t listen to music much any more.

Your hackles rise, but because it’s a pleasant afternoon and because it doesn’t seem fair to open fire with a salvo of Tosches-style freeform rage, you let it go. In your mind, they’re a bunch of beige-clad wets, thickening at the midriff as quickly as their politics veer to the right. Their entire experience of music was the mainstream fodder of the eighties and nineties – marketed to them in convenient lifestyle packages, designed to fit the allegiance group they associated themselves with. Indiekids, who swallowed the ideal of the slack-haired skinny guitarboys with poetic sensibilities and sharp cheekbones as an alternative to the powerballads and megamix pop that was what the proles bought.

Or perhaps they were once metalheads,

[quote]marketers divide the music-buying

public into ‘eclectic’, ‘experiential’

and ‘defender’ groups. If your CD

collection ranges from Bill Laswell

to Bach, guess which group you

fall into[/quote]

convinced that their chosen proponent of major-chord, twiddly-solo mini-epics were the only way to go. Maybe you once knew them as whistle-blowing, glowstick-waving, mong-eyed ravers, whose connection to a scene that was truly underground and subcultural proved them as the avant-garde of all that was gritty, urban, and real.

Whatever they once were though, they’re not now. And you’re forming a theory in your head about it. The theory is this: they were the gullible dolts for whom the music marketers developed minutely detailed subcultures in the post-war, economically fat era of jukebox milkbars, B-movies and politicians called Kennedy.

Things were simpler then, of course, because it was all virgin territory. Too many kids buying Beach Boys records? Create a new archetype, change the clothes a little, call in the stylists. The process developed for decades, but eventually, the music just became a small part of the overall package the kids bought. For your hosts, lugging a Sisters of Mercy twelve-inch around in a place where it could be seen was as much a part of their image-creation and allegiance efforts as eye-liner and frilly shirts.

The crucial part of the theory is that, as far as the actual music on the record was concerned, it hardly mattered. They only bought, listened to, sang along to and loved the music because it was a part of a larger set of artefacts and signifiers that defined how they wished to appear to their peers. And now those aspects are no longer important to them, because they have aged, mated, nested.

You are a smug sort, aren’t you?

As a music consumer of any sort, you are part of a group. Just as in Taoist philosophy (ask the people eating the pulled pork, they’ll know), the absence of energy can be considered as defining a characteristic as its presence. If you are determined to choose your listening material solely for its musical value, independent of the marketing strategies which surround it, fear not – the music business has a strategy for you nonetheless.

The broadest thematic groups used by music marketers divide the music-buying public into ‘eclectic’, ‘experiential’ and ‘defender’ groups. If your CD collection ranges from Bill Laswell to Bach, guess which group you fall into. If you’ve bought a piece of music, even if you’ve downloaded it for nothing, you have most likely been influenced by a marketing campaign of some sort or other.

That’s not what this post is about though – determining to what extent BigMusic has manipulated us into owning a piece of music that we may actually enjoy. That was just an exercise in exposing some of the emotional baggage we all carry around with us when it comes to our consumption of music. In some ways the 40-somethings who claim to no longer be interested in music display the more admirable of attitudes – they are so far removed from the channels of music marketing that they are unaffected by the need to keep up, to conform.

There are a couple of relevant tropes. One is that middle-age is a period where we are expected to be less interested in everything (perhaps a biological imperative focusing our attention on our offspring?). The other is a bit more chilling: maybe people only consume music because they feel they should.

The original premise in this rambling screed was to point out that people in middle age often state that they are no longer interested in music (neither recorded nor live) since they had kids/got a mortgage/turned 35/discovered PornHub, etc. This seems a discrepancy in what is normally seen as a gradual sophistication of sensory discernment as we age.

It is usually assumed (at least amongst the middle classes of the western world) that with age, our appreciation of the more challenging pleasures develops. We sip single-malt whiskeys; coo over pleasing architectural features; start caring about the threadcount of our Egyptian cotton sheets; we learn to identify the scent of lavender in a glass of Chateauneuf du Papes.

Ideally, we could lament the seeming lack of discernment in the ageing music consumer and leave it there, wondering why we collectively refuse to apply this developmental process to our musical pleasures? We could point out that, just as brandy cannot be appreciated by those under the age of thirty, nor can John Coltrane. We could have go on to assert that, what with the major preoccupations of adolescence (peer acceptance, love, getting a job, finding porn, etc) behind them, the opportunity to choose and appreciate music, unfettered by the artificial restrictions of teen-centered marketing, now present themselves.

Surely, with the western world’s demographics showing a slew to the late-thirties (median age of the USA: 36.8, Europe: 37.7), the music industry could present itself to this dominant age-group in a more attractive way. Posit music as an ethically-sourced high-value commodity, to be savoured by an ever more-sophisticated audience in the same way as they obsess over the smoky nuances of Blue Mountain coffee or the brittle temper of Valrhona chocolate? Form music-appreciation groups where attendees gather around vinyl copies of classic albums and nod appreciatively as the music plays (been done)? Covermount Adele CDs on organic veggie boxes? Blah blah.

But what if we’re all a bit more Homer Simpson than we are Noam Chomsky? Is it actually the case that, with a bit more age, experience and confidence, we actually manage to start ignoring a whole range of stimuli that were previously imposed upon us by some sort of perceived superego? Maybe people only really listened to music because they felt that they should. Perhaps musical knowledge was just one item in the experiential lexicon that was mistakenly assumed as necessary to present ourselves as valid members of society – and worthy of being taken seriously.

Could it be that music was never actually important to the spiralized courgette set, and that it only ever filled a role of social obligation that has now been replaced by the need to have an opinion on Paulo Coelho’s latest narrative structure or a decent supply of purple-sprouting broccoli?

There was always a sense of exclusive/inclusive snobbery involved in music consumption. Your music, and your willingness to display a degree of commitment to a chosen artist by buying the record was a crucial unit of currency in the economy of credibility, cool and social cohesion that made up the world of an 80s or 90s teenager. What it actually sounded like was hugely important, but the social repercussions were huge too.

Music’s migration via the Walkman and iPod to an individually-consumed artefact hasn’t had much effect on this social currency. When comments boards on newspaper websites state things like ‘well, now that FlyLo’s getting featured in The Guardian, we can definitely say that LA beats is over’ show clearly that the social baggage that surrounds music as a product survives even the iPod and filesharing. Allegiance, in the age of earbuds, is now displayed through knowledge of emerging subcultures and by attendance at live performances.

Nevertheless, given that you are reading Trebuchet, a source with an editorial policy on music driven mostly by gut feeling rather than glossy major label marketing campaigns, you are most likely not someone who listens to music for any of the reasons outlined above. You listen to it because it transforms you, nourishes you, moves you, plies the emotions you know about and plays with the ones you don’t have names for.

Despite its popular image, most of those working in the music industry are equally enslaved to the irrational physical and emotional feedback that music produces in us. Why would they be in the music business if it were any different? For the money? There are plenty of other industries out there, most of them a far safer bet for making money than the stumbling music biz (and let’s take the BMI’s recent jubilation about vinyl sales topping one million units as the admission of defeat it actually is).

Thing is, maybe we’re the freaks. Maybe the music industry is in freefall not because the kids are buying apps instead; or because it’s all getting pirated; or because everyone just listens on Spotify; or because the quality’s gone down; or because the market’s glutted; or whatever other explanation for the demise of the music industry you’ve heard.

Perhaps it’s just that most folk never really liked it much anyway.

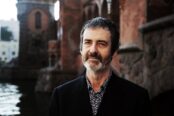

Sean Keenan used to write. Now he edits, and gets very annoyed about the word ‘ethereal’. Likely to bite anyone using the form ‘I’m loving….’. Don’t start him on the misuse of three-dot ellipses.

Divides his time between mid-Spain and South-West France, like one of those bucktoothed, fur-clad minor-aristocracy ogresses you see in Hello magazine, only without the naff chandeliers.

Twitter: @seaninspain