[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]ith the rise of the art market from a small community to a global industry, it is easy to deride private collectors as commercially driven egotists who collect as a display of their wealth.

This view does not, however, give recognition to the role that individuals have played in the accumulating and preservation of some of our greatest works.

It fitting therefore that, the first thing to strike the viewer upon entering the anteroom at the top of The Courtauld’s winding staircase, is an ethereally white bust placed in lieu of the iconic Tahitian paintings that one would usually envisage upon hearing the name ‘Gauguin’.  This juxtaposition between the sculpture, which depicts the artist’s wife, the Danish born Mette-Sophie Gad) and the infamous ‘Te Rerioa’ masterpiece featured upon the cover of the exhibition catalogue, initially appears incongruous.

This juxtaposition between the sculpture, which depicts the artist’s wife, the Danish born Mette-Sophie Gad) and the infamous ‘Te Rerioa’ masterpiece featured upon the cover of the exhibition catalogue, initially appears incongruous.

In post- exhibition retrospect however, the placement of the bust serves as a motif for the emphasis of the show upon the relationship between artist and collector that, has ultimately cemented Gauguin’s canonical status.

It was not always the case. After the first major showing of Gauguin in Britain as part of Roger Fry’s now-renowned 1910 exhibition, his work was conspicuous for its absence from the subsequent group Post-Impressionist showcase of 1912. As a counter point, none of Gauguin’s works that went on to constitute Courtauld’s personal collection were present in the 1910 hanging.

Rather, it appears that his financial commitment to the painter began some ten years later at what would first appear to be a counter-intuitive time. At this point critical reception was focussed more on Gauguin’s contemporary ( the golden boy, Cézanne) whilst collectors’ continued acquisitions of the former were pushing prices increasingly higher.

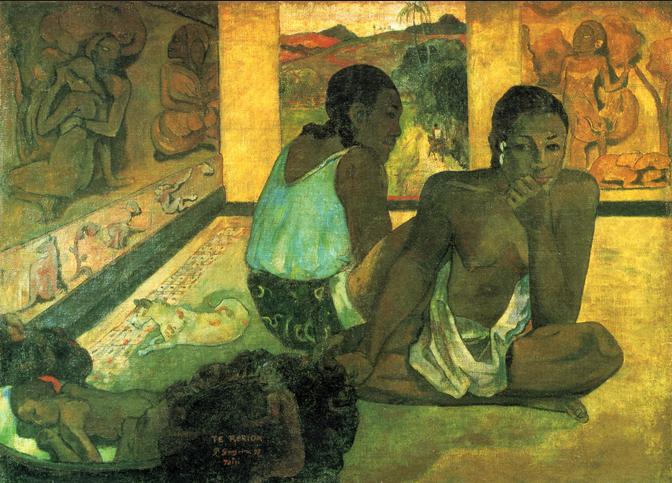

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) ‘Te Rerioa’ (The Dream), 1897 Oil on canvas, 95.1 x 130.2 cm

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) ‘Te Rerioa’ (The Dream), 1897 Oil on canvas, 95.1 x 130.2 cm

© The Courtauld Gallery, London

Courtauld’s interest can therefore be seen to be not so much for financial profit as a genuine support of Gauguin’s style. Indeed, his first purchase of ‘Les Meules’ (1889) and ‘Bathers at Tahiti’ (1897) came in the wake of the opening of Fry’s loan exhibition: The French School of the Last Hundred Years at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, where Gauguin was represented solely by Sadler’s ‘Manao Tupapau’.

Despite his stayed hand, Courtauld became Gauguin’s most regular patron, purchasing on average a piece a year up until 1932 and, even pioneering the re-energising of interest in the painter on the British Market.

The bust speaks much for the development of this powerful relationship. Although, not immediately captivating in terms of Gauguin’s idiosyncratic bold form and colour, it is a beautiful object in its own right- epitomising Courtauld’s curatorial approach based upon aesthetic preference rather than market trends.

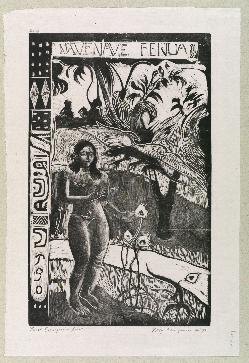

The presence of the incredibly intricate woodblocks from the Noa Noa sereis, reprinted by Gauguin’s son in 1894, also pay testimony to this. Hovering in status between highly rendered sculptural surfaces – similar to those depicted on the bust – and illustrations; they evidence an artist with a focus upon technique and careful attention to surface and form.

This focus is continued into his paintings in the choice of coarse canvas to evoke a simpler mode of living and it is details such as this that so appealed to Courtauld’s instinctual preferences.

In contrast, the initial critical mania for Gauguin’s work in 1910 had been as much to do with a celebrity focussed interest in the life of a man who had lived amidst primitive, far-flung communities, as much as the paintings themselves. This is apparent in the poster for the Grafton Galleries’ show, which depicts Gauguin’s ‘Poemes Barbares’. It is unlikely that the work actually made it across the channel in time for the show but it is demonstrative of the fascination in the mystique of ‘the other’ and cult of the well-travelled artist.

This is neatly illustrated in Collecting Gauguin by the adjacent positioning of the photographic portrait of the artist, which looms at the edge of the exhibits, almost as a collectable artefact in itself. Indeed, much of the popular intrigue surrounding ‘Te Rerioa’ stemmed from the rumour that it represented the interior of Gauguin’s house in Tahiti.

In light of this it is unsurprising to learn from Dr Karen Serres, the curator, that when Gauguin announced his intention to return to Europe to continue painting, his friend and dealer in France, Daniel de Monfreid immediately protested that it would be the end of his career if he did. This is in spite of the fact that many of Gauguin’s paintings borrowed figures from studies of European origins, suggesting that the cult of the romantic nomadic artist was still very much at play.

On the other hand, Courtauld literally lived with his collections and so it was the physical composition of the work itself wherein his main interests lay, purchasing for long-term investment into a preferred style. Indeed, all of these works were at one point collectively present within the collector’s house exemplifying Coutauld’s admiration for their decorative element rather than the academic interest that drew him to Cézanne. This may indeed go some way to explaining why he turned down the opportunity to purchase what Gauguin considered his greatest masterpiece – ‘Where do we come from/What are we/Where are we Going’; 1897-98. As symbolically loaded as its weighty title suggests, it may have been conceptually brilliant but, in terms of Courtauld’s emotional identification, it did not merit his investment. The current show, therefore, in some ways acts, not so much as a gallery environment but as an intimate recreation of the works’ original domestic setting.

Dr Serres notes that the display does feel a little crammed for her liking, however, the slight claustrophobia does go some way to hint at this exceptionally personal relationship between curator and artwork. Indeed, even the inclusion of some of Gauguin’s sketchbook drawings – which cannot be absolutely verified as being purchased by Courtauld – may have been applauded by the collector. One of his driving concerns was the expansion of public engagement with modern art, in light of the business acumen of Parisian dealers such as Ambroise Vollard pushing market values of work far beyond the means of the average buyer. It was time to save work from disappearing into the vaults of affluent German and Russian buyers.

[quote]Courtauld literally

lived with his collections

and so it was

the physical composition

of the work itself

wherein his main

interests lay[/quote]

This he did through loans of both art and funds to public galleries, establishing the Courtauld Fund for the purchase of modern French art in 1923. Notably the the fund ran out before any purchase of Gauguin’s comparatively highly priced works could be purchased, leaving it up to Courtauld to invest privately in the painter. This emphasis by Courtauld on accessibility to art makes the inclusion of two loans in this show of ‘Martinique Landscape’ (Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh) and ‘Bathers at Tahiti’ (Barber Institute of Fine Arts) not uncomplimentary to the original ethos of the display.

The drawings themselves reveal the skilled draughtsmanship of a painter predominantly noted for his stylised, abstracted forms, adding a further layer to our understanding of the aesthetic beauty that captivated Courtauld’s imagination. The curation of the show in chronology of production rather than purchase also neatly dovetails this notion.

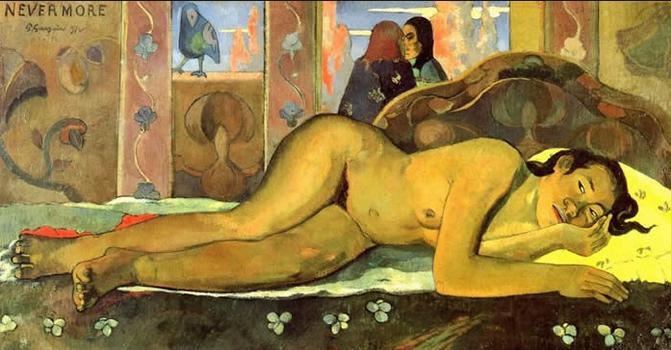

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) ‘Nevermore’, 1897 Oil on canvas, 60.5 x 116 cm

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) ‘Nevermore’, 1897 Oil on canvas, 60.5 x 116 cm

© The Courtauld Gallery, London

Evident is the development of Gauguin’s style from the rapid brushstrokes of the early Martinique landscapes which, with their ‘safe’ Impressionist overtones were an early introductory purchase for Courtauld, through to the heavier dark lines and defined forms that find their zenith in the three Tahitian nudes of ‘Nevermore’, ‘Te Rerioa’ and ‘Bathers at Tahiti’. The vibrancy of these three paintings, united on the gallery’s central wall, pays testimony to Courtauld’s instinctual fascination with ‘the sensuous colours’ of Gauguin’s paintings and his subsequent dedication to these instincts.

Fry (as evidenced in his letters) had in fact advocated selling ‘Nevermore’ to purchase ‘Te Rerioa’, upon his reinvigorated interest in Gauguin when visiting Paul Rosenberg’s in Paris. Courtauld eventually owned both, having purchased ‘Te Rerioa’ for £13,600 in 1929.

Thus, alongside the evolution of Gauguin’s style we can also witness the emergence of two schools of collector. On the one hand stood those such as Michael Sadler, a leading writer on educational theory who, up until the 1920s held the greatest concentration of Gauguin’s works in private collection.

Sadler epitomised the approach of collector’s such as Charles Saatchi today, selling work according to changing interests and trends in order to invest in new pieces. An early champion of Gauguin’s work, it is telling as to his buying style, that one of his purchases was the mythical ‘Poemes Barbares’ discussed above. His Gauguin collection was notably dispersed in the 1920s due to financial constraint and shifting market trends.

On the other hand stands Courtauld with his steady investment and trademark focus upon personal taste, looking to acquire a lasting testament to that taste through his collections. The selling of ‘Martinique Landscape’ and ‘Bathers at Tahiti’, therefore, marks more a growth in confidence in Gauguin’s later style and bolder palette than a calculated financial move.

The Courtauld’s choice to exhibit Gauguin can therefore be seen as an apt entry point into this unique instinctual approach on the part of the institute’s eponymous founder.

Collecting Gauguin gives us both a stunning account of the developing style and varied technique of one of our most renowned painters and reveals the determination and attitude of the man responsible for our ability to view this variety – rather than simply a homogenous depiction of 1920s critical taste.

Collecting Gauguin: Samuel Courtauld in the ‘20s

20 June- 8 September 2013

For Tickets and Information see The Courtauld website

Side images:

1. Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) ‘Portrait of Mette’, 1879-1880 Marble, 34 x 26.5 x 18.5 cm

© The Courtauld Gallery, London

2. Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) ‘Nave Nave Fenua’ (from the Noa Noa series), 1893 (published in 1921)

Wood engraving, 33.4 x 20.4 cm

© The Courtauld Gallery, London

3. Interior of Samuel Courtauld’s residence, Home House, Portman Square, London, c. 1930

with ‘Te Rerioa’ (The Dream) on display

© The Courtauld Gallery, London