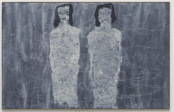

Lee Bae, Landscape (detail)

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]M[/dropcap]inimal Art, it has been argued, is the dying breath of abstraction, and painting more generally (Winters, 2018).

After Clement Greenberg’s insistence that paintings should be flat (they are) and should be seen to be flat (arguably, they are) representation was to be abandoned by painting as an illusion – the whiff of fraudulence and trickery recruited to demonise figurative paintings.

What this abandonment achieved was the removal of any sense of what painting, as a representational medium, was meant to be. In effect flat coloured expanses became just two-dimensional sculptures. So, Minimalism took on the third dimension and no longer needed colour, now seen to be ornamental.

In Paris, however, there is a show with work that might easily be passed off as Minimalist. It is not.

(Or if it is, it demonstrates a quiet and quite gentle return to the image as revelatory.) Pre-Minimalist artists outside America’s later influence provide insight into how we might best think of Bae’s work.

Mies van der Rohe, the German architect and furniture designer, gave us “Less is more;” and “God is in the detail.” Together these two aphorisms make us look closely at that which we might ordinarily pass over.

Constantin Brancusi, the Romanian sculptor, gave us Endless Column. Brancusi’s sculpture never had to arrive at abstraction from naturalistic image making, since he worked in a tradition that paid no heed to the strictures of the Western canon.

Both these modern masters belong to a kind of art-making that takes us out of the European tradition and into a form of Modernism that had nothing to do with the flatness of the canvas giving way to the rise of sculpture. Each, in his own way, challenges the notion of an image and its composition.

Lee Bae, “Black Mapping” exhibition at Galerie Perrotin, Paris (photo by Claire Dorn. Courtesy, Perrotin)

What is an image? The imagist poets were a group of American/English poets, led at the beginning by Ezra Pound, writing at the beginning of the last century. Influenced by the French modernists’ vers libre, they wanted to forge a new poetry that would concentrate on the image rather than the poetic devices that had constrained Victorian writers.

They were to find in everyday life truths that could be made imagistic, rather than great abstractions that were contemporarily dominant as themes for the poet. Here is Pound on the (poetic) image:

The Image can be of two sorts. It can arise within the mind. It is then ‘subjective’. External causes play upon the mind perhaps; if so, they are drawn into the mind, fused, transmitted, and emerge in an Image unlike themselves. Secondly, the Image can be ‘objective’. Emotion seizing upon some external scene or action carries it in fact to the mind; and that vortex purges it of all save the essential or dominant or dramatic qualities, and it emerges like the original.

In either case the Image is more than an idea. It is a vortex or cluster of fused ideas and is endowed with energy. If it does not fulfil these specifications, it is not what I mean by an Image. (Jones, 1972)

The imagists were attempting to create poetry out of the everyday, and to make its language as much like the language of everyday speech as it could. Gone were the haughty aestheticisms of the Victorians with their high-blown airs and graces. Imagism was to celebrate the modern, and if that meant overhauling the language of poetry, then so be it.

By 1918 Poetry [magazine] was able to say:

‘Free verse is now accepted in good society, where rhymed verse is even considered a little shabby and old fashioned.’

(Jones, 1972)

As might be imagined, the imagists met with some fierce resistance. But in a piece of criticism, the critic unwittingly spells out what it is that is so convincing about their work. Commenting on the fact that the Imagists had turned away from the monumental themes of poetry, we are told,

‘[Some Imagists] were so terrified at Cosmism that they ran into a kind of Microcosmicism, and found their greatest emotional excitement in everything that seemed intensely small.’ This of course [T. E,] Hulme would have approved with his own ‘It is essential to prove that beauty may be in small, dry things.’

(Jones, 1972)

With the lessons of the Imagists in mind, it is worth considering the work of Lee Bae, currently on show at Galerie Perrotin in Paris.

Bae works great slabs of charcoal, planning them and finishing them to an even flatness that stand proud about 3cm from the surface of the creamy-white canvas supports upon which they sit. The creamy-whiteness serves as a warm ground and sets off the burnt charcoal as a dense sepia black, therefore contrasting the charcoal colour without resorting to plain white.

The ridges that the thickness of the charcoal makes against the canvas house dust and this has a ‘drawing’ quality about it, as if the line of the charcoal, where it meets the white, has been scuffed and rubbed to render the ‘drawing’ easier on the eye. It also suggests the dust of a ridge that goes unwiped, so that a kind of life of the object begins to appear before us.

The imagists were concerned with images that weren’t pictures – mental images. Minimalism cleansed the painting of illustrative, figurative images. The beauty of small things is a kind of attention that these poets used to adjust our sensibilities.

Bae’s work uses process and colour (the whites aren’t white, and charcoal isn’t black) to make us aware of the materials with which he works and to draw our attention to the nature of the machining that these works have had to go through to achieve their remarkable surfaces.

If these works are to be considered as images, then they are revelatory images; in that they draw our attention to things unseen heretofore.

They are very beautiful objects; and they contain complex imagery.

Edward Winters

Copyright, Lee Bae.

Installation photograph by Claire Dorn.

Courtesy of Galerie Perrotin

References:

Peter Jones (ed., and intro.) Imagist Poetry, London: Penguin Books, 1972

Edward Winters, ‘The World is Not Enough’, in The Monist, volume 101, issue 1, January 2018

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.