[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]ood, lovely, lovely wood.

Knowing that your building has lived, has been subject to the same environment as you, that it now serves to enhance (or protect you from) that very environment: it’s emotional. Spheron Architects acknowledge, even foreground that ability of great architecture to trigger memories, communicate feelings and evoke emotions. With offices in both London and Accra, the firm avoids a signature style of recurring visual attributes in its commissions, instead approaching the task of design with a view to instilling buildings with meaning, with human resonance.

Whilst it may be reductive to focus on just one project, the Belarussian Memorial Church designed by Spheron Architects in 2016 is a case in point, evoking tradition, history, spirituality and scale in one swoop. Director Tszwai So explains the ethos.

Can you describe the first moment architecture captured your imagination?

It made me emotional before any reasoning took place, just like art and music, it made me feel human and whole. It was always those unassuming buildings or places that triggered this feeling – like those unpretentious vernacular wooden churches in rural Belarus. They made me want to simply sit down beside them and watch my whole life go by.

How do you judge great architecture?

There was the famous Pevsner definition: ‘architecture has to have an aesthetic appeal.’ But for me, utility is a given, what distinguishes a piece of architecture from simply a building is its emotional appeal, it takes you to an inner beautiful and peaceful place in the absence of words.

Some architects consider light as an intrinsic material in their designs, is this the case in your work?

Light creates atmosphere; it makes materials instantly become tactile, the right lighting can express emotion and relay a message far better than words.

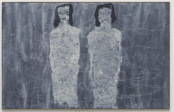

For example, in Urban Hermitage, I wanted to recreate the solitary urban interiors of the early 20th century Copenhagen as depicted by Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi. The purpose of installing the translucent curtains was to diffuse the harsh and direct sunlight since the room was facing south, in order to bring out the quality of the subdue blue and grey-themed textures in the room.

At the entrance of the Belarusian Memorial Chapel, the whole of the south-facing facade has vertical ribs interspersed with frosted glass, taking advantage of low-angle winter sun to provide beneficial solar heating and at the same time diffusing strong and direct sunlight which is hostile to the religious icons inside.

On the other hand, the lateral walls are enormous slabs of laminated timber with a clerestory window and a band of frosted glazing at the base of the walls, giving the wooden walls the impression of hovering between the two bands of light, belying the initial impression of huge solidity. At night, soft light from within allows the chapel to glow gently, referencing the WWII atrocities committed by the Nazi troops, when Belarusian wooden churches full of people seeking sanctuary were set ablaze.

….

The full version of this interview will appear in the printed edition of Trebuchet Magazine available to pre-order here.

Image: Joakim Boren

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle