[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]D[/dropcap]ouglas Adams was right all along (again).

Not content with commissioning a planet-sized supercomputer to dig out the meaning of life, it turns out that mice are also teeth-gnashing coke fiends. No wonder their eyes are pink.

Cocaine can speedily rewire high-level brain circuits that support learning, memory and decision-making, according to new research from the University of California, Berkeley, and UCSF. The findings shed new light on the frontal brain’s role in drug-seeking behavior and may be key to tackling addiction.

Looking into the frontal lobes of live mice at a cellular level, researchers found that, after just one dose of cocaine, the rodents showed fast and robust growth of dendritic spines, which are tiny, twig-like structures that connect neurons and form the nodes of the brain’s circuit wiring.

“Our images provide clear evidence that cocaine induces rapid gains in new spines, and the more spines the mice gain, the more they show they learned about the drug,” said Linda Wilbrecht, assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience at UC Berkeley and lead author of the paper to be published August 25 in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

For mice, “learning about the drug” can mean seeking it out to the exclusion of meeting other needs, which may explain how addiction in humans can override other considerations that are necessary for a balanced life: “The downside is, you might be learning too well about drugs at the expense of other things,” Wilbrecht said.

[quote]For mice, “learning

about the drug”

can mean seeking

it out to the exclusion

of meeting other

needs[/quote]

Previous analyses of postmortem mouse brains have shown that repeated cocaine use and withdrawal changes dendritic spine density after weeks of exposure. But this is the first time that 2-photon laser scanning microscopy has been used to make images of spines in the frontal cortex before and after the first cocaine exposure in living mice, Wilbrecht said.

Over the course of a few days, male mice were moved from their cages to a “conditioning box” comprised of two adjoining compartments. Each chamber – one smelled of cinnamon and the other of vanilla – was decorated with different patterns and textures so the mice could differentiate between the two.

Initially, the mice were free to explore both chambers, which were connected by a small doorway.

Researchers recorded which side each mouse preferred. The next day, the mice were injected with saline, which has no stimulant effect on mice, and were placed for 15 minutes in the compartment for which they had shown a preference. The door between the two chambers was shut.

The following day, they were injected with cocaine and placed in the chamber that was not their preferred side. Again, the door between the two chambers was shut and they were inside for 15 minutes.

On the fourth day, the door between the two chambers was open, yet the mice overwhelmingly picked the chamber where they had received and presumably enjoyed the cocaine.

“When given a choice, most of the mice preferred to explore the side where they had the cocaine, which indicated that they were looking for more cocaine,” Wilbrecht said. “Their change in preference for the cocaine side correlated with gains in new persistent spines that appeared on the day they experienced cocaine.”

According to Wilbrecht, “These drug-induced changes in the brain may explain how drug related cues come to dominate decision-making in a human drug user, leaving more mundane tasks and cues with relatively less power to activate the brain’s decision-making centers.”

Source: University of California – Berkeley

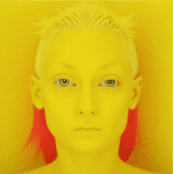

Image: Freedigitalphotos.net/Victor Habbick

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.