[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]R[/dropcap]eeves Gabrels is known for fearless improvisation and the creation of huge sonic landscapes.

If he had a strapline, it would probably be ‘refreshes the fretboard parts other guitarists can’t reach’. So has regularly playing to anything from 30,000 to 150,000 people gone to his head? Not a bit of it. He’s great company – a charming man with a self-effacing sense of humour, who simply describes himself as ‘a guitar player having fun’.

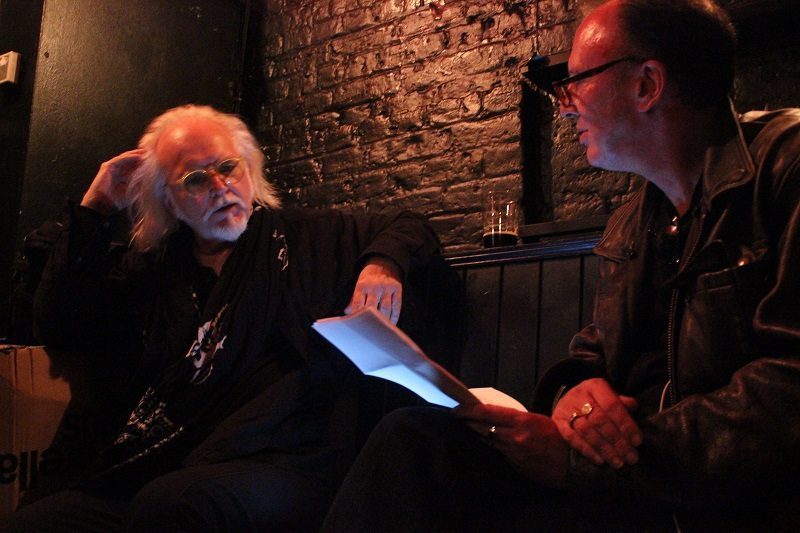

Before a performance by his power trio, to promote new album Reeves Gabrels and His Imaginary Friends, we shared a beer at The Black Heart in Camden, and chatted about songwriting, touring with Bowie and The Cure, re-claiming the blues and crawling across the floor on all fours to feed the cats (amongst other things)….

You’re known for pushing the boundaries as guitar player, through improvisation and adventurous arrangements. But the songs on your new album have pretty classic constructions and strong hooks. ‘Wish You Were Her’, for example, sounds very much like a classic pop song. Which generally comes first when you write – guitar riff or chorus?

I never know! I guess it’s different every time. But that track is one of my favourites.

So, were the songs on Imaginary Friends written individually, or did they develop organically with the band?

A song like ‘Drown You Out’, Kevin Hornback, the bass player, had the basic idea for that, with a lot of the lyrics. He showed it to us, and I changed a couple of things, changed a couple of chords and added a bridge. But a lot of the time I’ll just demo things at home with an acoustic guitar, and then play that basic idea to the band – then we’ll arrange if from there. But because of the way I like to play, it’s like I feel I always need a strong structure, because then the song can really stand up to stretching and pushing harmonically.

That feels like a classic rock song too. I can even see other bands covering some of the tracks on this album. Maybe not the guitar solos though….

Yeah! It would be great if somebody wanted to cover one! I’d like that. But going back to something like Tin Machine, a lot of people though that I was the one trying to explode the song form, but it was David that was actually the one that was subverting things. I was the one bringing what I thought were more pop songs, and he was the one that was twisting things more. But then once we got it up and running the guitar player part of my brain would take over and I’d start to twist things too.

‘Won’t fall In’ on the new album I wrote with my friend Jamie Rubin, who owns a club in Nashville. He and I wrote that with a fella called Dave Hull who is a bass player. The three of us just got together. Someone had a verse, someone else had a chorus. ‘Try’ is another one that came from Jamie and me. A true collaboration. I like that – you never know where it’s going to go.

‘Zero Effect’ is a song with a bit of everything. Acoustic intro. Huge riff. Ambient ending….

‘Zero Effect’ had 5 different writers on it – including me! I wrote the riff for another project. And then I had a band together in LA called Engine Room, and we turned that riff into the first part, the main meat of the song with the chorus, then the drummer with the band said, ‘It needs a different outro. It needs something like the way The Who had that little reprise at the end of Tommy… ‘Listening to you…’ So I wrote a piece like that for the end.

Then the acoustic intro… I was just sitting in the lounge at the studio playing an old guitar, and Rob Stennett, who co-produced the album with me, heard it and said ‘That sounds great!’ and he put a mike up and I just did a bunch of little bits to see what it would sound like. Then later I was singing the chorus and outro of ‘Zero Effect’, and I had the idea to edit that together and put the acoustic bit at the front of the song. But the problem was, it wasn’t in standard A440 – it was in the cracks of the piano! So we took a harmonic I played at the end and bent it electronically into the key of the song with a plug in on the computer.

The beauty of the way we record now with Pro-tools etc., is that you can sort of tear at the fabric of reality. If we’d have had Pro-tools when we were doing Tin Machine for example, things would certainly have ended up sounding different.

On the other side of it, there are things like those great Beatles doubled vocals or Lennon when he doubles his own vocal that wouldn’t have happened with that technology. Because, I believe, it was an attempt to hide the ‘pitchiness’ of the vocal, by doubling it.

Now of course you’d just autotune it – which is one of the things, as a point of pride that we haven’t done on the new album. But I want to try playing slide with autotune on it – that what I’m curious about! Let’s see what happens there.

So you enjoy working with other people, because there’s only so far you can go on your own. You enjoy collaboration.

Absolutely. And some songs, like ‘Zero Effect’, are written over period of time. That was looking for a home for maybe ten years! It kept changing. But it’s a lot more fun to collaborate. The whole idea of this band, The Imaginary Friends, is the fact that I’m trying to take the power trio concept and bring it into the future. The fact that anyone can change their part at anytime during the night kind of makes it into a conversation. It’s a constantly evolving thing.

You have a big reputation for improvisation. Is there more room for that in this band, rather than the more structured arrangements with Bowie and The Cure?

Actually there is still room for me to experiment with The Cure. I find there’s usually a bit of room in everything I do.

So live, do you ever actually play the same solo twice?

I sort of do, if it’s a ‘known solo’. But the good news and bad news is that none of my own songs are that well known enough that people will sing along to the solos! So I can play them differently. But when I play with The Cure there are some things where the audience knows the solo note for note and are singing along with it from when you start, so you need to play those solos, even if they were actually improvised at the time, just as they were.

Over time you develop a sense of what’s important to the song, and what’s important to your own ego. In The Imaginary Friends we stretch some sections sometimes. Sometimes it’s in a look, sometimes maybe there’s a melodic figure I have that they know means we’re moving to the next section. That could be after 8 bars, or maybe sometimes sixteen… or whatever.

So eye contact with the other guys is important?

Yes – but eye contact isn’t as important as listening. I always think that when you are playing together it’s sort of all happening ‘up here’. Like a virtual creative room that you all enter and there’s someone else controlling you. We’re kind of like Kraftwerk up there! We’re just big puppets and we’re really somewhere else controlling it all!

‘An Inconvenient Man’ stands out from the other tracks. It feels kind of like a move soundtrack – is that something you want to do more of?

Yeah – I’ve done of bunch of film stuff. But even some of my older solo albums all have a little bit of more ambient textural stuff. But I’m really not a fan of instrumental rock guitar records. ‘An Inconvenient Man’ actually happened the same day I did the acoustic intro of ‘Zero Effect’. I plugged some pedals in and I had about 20 minutes of all these improvised things.

I listened to it with a friend of mine called Roger Nichols, who mixed the record, and we kinda just thought, oh this piece is a nice section, let’s cut that in, cut that out, and this could go next to that. Interestingly, if you put the CD on and put it on rotation with ’13 Steps’ at the front and ‘An Inconvenient Man’ at the end, they all bleed well into each other and it just goes naturally round and round….

You worked with both David Bowie and Robert Smith – two very distinctive writers. Do you find a bit of their writing style has rubbed off on you?

I’ll never know – I’ve only written maybe four songs with Robert, so it’s hard to tell. It’ll be interesting to see what happens there, over time. And a lot of what we did on Earthling and Hours and even the Tin Machine stuff – well, it’s a good debate. But I wrote 52 odd songs with David… so I don’t really know any longer. But then I suppose my style influenced him too – so it’s a tough one.

You wrote a lot together in Tin Machine. Was the sound of the band Bowie’s idea, or did your guitar style lead things that way?

It just became that. We were talking about what David wanted to do. He and I talked about what he liked, versus what he had ended up doing by the time he did ‘Never Let Me Down’. So I just said well, why don’t we go after the music that we are both listening to? Because we were both listening to almost identical stuff.

As a band, we knew what it wasn’t going to be – everything is defined by its limitations to some degree. So we knew we weren’t going to have keyboards, we knew we weren’t going to have any electronics on it. We knew it was going to be organic.

Talking of organic, you’ve got a bunch of blues songs on Imaginary Friends….

If you count ‘Who Do You Love’ as a blues song! I think of it more as R’n’B – but that’s splitting hairs.

Whether they are Blues or R’n’B, with these versions you totally own them.

Yeah, I’ve rearranged them. ‘Bright Lights Big City’ is re-harmonised. Though it still follows the 12 bar thing. ‘Messin’ With The Kid’ has that turnaround, which I haven’t counted in a long time, but I think it’s 3 bars of 7/8, which you don’t usually get in blues! Ha! We stitched things together so you get, I don’t know, Junior Wells meets Yes! Then there’s ‘Who Do You Love’. I always thought that the lyric of that song was why it always got overlooked. If you really look at the words, they are some incredibly evil and creepy lyrics. So I wanted to make it about the words, and the atmosphere I thought they evoked. And you know, when you are making a record it should be a part of you, it’s not a commercial endeavour at this point – it’s just another entry in the journal.

This record is very user-friendly, if you like. Whereas a previous solo record like Personal Nuclear Assault is more experimental and maybe much harder for a new audience to get into.

Ha! Actually that was just two nights – one night in New York and another in Switzerland, and it just happened to get recorded. Somebody mixed it, and the next thing I knew it was out. It wasn’t ever recorded to be released – we just discovered we had an album’s worth of stuff.

So Imaginary Friends is very intentionally aimed at a wider audience. With a focus on the songs, not just the musicianship?

Yeah, sure. But to go back to the blues songs, you know, that’s part of my roots. So I want to keep those songs alive, or have some kid go, ‘Hey, they say this is blues… let me look up what blues is’. So they’ll go back to the source, instead of to that sort of blues librarian that has become popular, where they’re doing a Howlin’ Wolf song and playing the Hubert Sumlin solo note for note – with all the mistakes.

I love Hubert Sumlin, but I think the idea of doing something that opens it up to a new audience is great. Something that ties you to a tradition but also turns people onto the originators without copying them – you’re trying to breathe new life into it. Hopefully I’ve succeeded.

Current radio is very straight and staid – do you think the way you push things limits your exposure? What sort of stations pick you up.

I have no idea! It would be nice to have more airplay, but it’s the internet stations now which are like the old local stations and what used to be college radio stations – where you’d go visit the stations and play a couple of songs and then in that little area you were on the playlist. And that’s what the internet can do. That’s what’s exciting about it.

But the whole idea of making music for a commercial end or to suit a market – if you think you know what sells. Well, there are two things. There are people that think they’ve got it all sussed and they can write hit songs and that’s what they do with the intention of making a lot of money. And then there are the people that don’t but still chase that. I’ve been doing it too long to care!

Your guitar style, it seems, is more about creating sonic landscapes, as opposed to just being a traditional guitarist. Do you see yourself as a musician in the wider sense than just being labelled a guitar player?

Yeah, I certainly do some things that are different. But I’m just a guitar player having fun. And I don’t even see it sometimes in musical terms, I see it as… well, I’m just another one of those guys that came out of art school. But then I made a left and went to music school. I went to Berklee. I’d taken some lessons from John Schofield when I was in the School of Visual Arts in New York and he talked me into going.

So you believe in learning all the rules first, before trying to break them break them?

Yeah, that’s my whole thing. At the point where I started playing there wasn’t a Mike Stern. There wasn’t anybody playing Jazz standards with distortion. That was something you just didn’t do, so when I started to want to do that, I felt like I had to be able to meet the older guys that were playing on their own terms – to earn the right to do it my way.

Having said that, there are plenty of people that come up with some amazing stuff that are completely ignorant of any rules, so there’s room for that too. But I actually enjoy meeting people I can discuss harmony with and stuff like that. You know the old joke was that when rock musicians got together they talked about gear and equipment and when jazz musicians got together they talked about harmony. I like to do both.

What advice would you give to a guitar player to help them get out of that rut of running through the same scales and modes, night after night?

You know it’s good to listen to everything that’s out there. Be aware of as much stuff as you can. Listen to everything. The whole idea of copying someone is pointless – if you’re copying it means there already is one! So why do it?

Over the years you’ve played a bit of every single sort of style – which must affect your note choices now… it must all meld and influence.

Yeah… actually there’s about a three month turn around for me. Like for a while I was into this guy who’s an Oud player, and it took about three months for his stuff to start popping out. That seems to be about my processing time. So I get into all sorts of stuff – the Bulgarian choir thing about 20 years ago. I enjoy the throat singers of Tuva, Bartok’s string quartets, or even Balinese monkey chants! If you find something in it, great.

There’s a group that I play with, who I’ll be doing some gigs with in Boston in November, called Club d’Elf. The joke being it’s actually ‘Clubbed Elf’! It’s fronted by bass player Mark Rivard, and John Medeski and Dave Tronzo have been in it. It’s an improvising collective. I remember there was one night when this guy Brahim Fribgane was playing Oud with the band, and I misheard the song. We get handed two or three pages of the song at the start of the show – the melody and suggested chord changes – but that’s it. So the song could be 10 minutes, 2 minutes or half an hour or whatever. But the bass player called one song, and I was hearing a Delta Blues. So I started playing John Lee Hooker type stuff. Then when I heard the recording later, I realised it was actually a big North African thing!

But you know it made perfect sense – because it was like the equivalent of blues from each area. Everyone took a cue from that and brought their own sense to it. And I love that. Again it’s a conversation – you discover what people are like as you play with them.

You were really very ill a while ago – do you think that understanding the fragility of life has helped you be freer and more adventurous?

I had Lyme disease – and a bunch of other things. I really used to dislike it when people say they wouldn’t change anything, but, you know, I actually wouldn’t. I went legally blind and lost my equilibrium, and I was living in a house by myself with a couple of cats and I was having to crawl on my hands and knees to go feed the cats or go to the bathroom. I had to put reflective tape on the corners of tables to stop bumping into them. That lasted a few months or so. I couldn’t watch TV or read. All I could do was lay in bed and listen to the radio. I was so weak that I had to put really light strings on the guitar and tune right down just to keep playing.

So I did a lot of work in my head instead. Mentally sorting out the closet and stuff! And since then, I can lay in bed at night and play guitar in my head and hear the notes. And the notes are right! But that also comes from doing it for 40 years too.

You do big tours with Bowie and Cure – using big rigs – now it’s tiny pubs. How does that feel?

Well the reason we’re doing this is that I do like to see the whites of the audience’s eyes, and I like hearing the reaction and what they have to say. It certainly isn’t for the money! We used to use the term ‘lifer’ – and that’s what I am. When I‘m finished with a big tour, the first thing I want to do is go out and play. In a way I play for 30,000 to 150,000 thousand people a lot, so these kind of small gigs are hard to find for me. It’s the old apples and oranges thing. They are completely different things. I’ve learned a lot about communicating with a large group of people, which is very different to doing these small gigs.

What’s great about the Cure is that it’s so tribal – this big emotional thing for this large body of people. To me, that’s a sacred thing – I want to make sure that it’s everything that they want it to be and doesn’t ever disappoint. I always figure that if I’m playing here, or the Albert Hall, the O2 or a festival or whatever, and somebody comes in that hasn’t had the best day – bummed out about something – if they leave feeling better, if I can be lucky enough to give them goose flesh at some point and create an emotional, cathartic experience, then I’ve earned the right to do it again another day.

You met David Bowie I believe through a love of art… does your interest in art influence the way you play and compose?

Yes, I originally met him through my wife. And yes, I do often think it terms of shape and colour. One of the things that happened early on was, when we were rearranging Look Back in Anger for a dance company, David said, ‘This should be like German Gothic Revival architecture. And I was like – OK! And he will often say things like, ‘This one should be like Jackson Pollock… this one should be like Salvador Dali – not melting watches, but your guitar that’s melting…’

After you reach a certain technical point it’s then all about living a life and bringing that to the stage. In that way it’s very much like what the blues and jazz guys were doing – or any artist. You bring your day to the stage and exorcise your demons. That’s what writers do, and all the great performers, and I’ve always aspired to that.

John McGlaughlin says, ‘Don’t get up on stage if you’re not going to leave some blood up there…’ And he’s a real gentleman, so for him to say something as tough as that, you know he means it!

Great Guitarist. And talking of great guitarists, I loved the stuff you did with Bill Nelson too….

Thanks, yeah. He’s the sort of guy that’s always moving. By the time he’s given a label, he’s already moved on. He’s not shy – he’s soft spoken, but he really knows what he wants. He’s one of the best players I’ve ever played with. He can play everything – he’ll sit and play Gypsy Jazz or Chet Atkins or How High the Moon – he’ll go any direction at anytime, and can play it all.

You’re known for using a lot of effects. Do you know the sound you are looking for in your head, or do you just experiment and see what happens?

It’s a bit of everything. I used the Kaos pad for a while, which was made for DJs. That was fun, but I’ve stopped using that – though it may come out somewhere again. I would need a time machine to get what I really want – to be able to manipulate the sound before it actually happens. That’s what I’m looking for now! Somebody said to me once that watching me play is like watching a Japanese monster movie that has been dubbed in English! I’ve seen enough video of myself to know what they mean.

Watching you play does have the unfortunate effect of making me want to go home and burn my guitars if I’m honest.

Don’t! Hey, I remember when I saw Adrian Belew the first time with Talking Heads and he blew my mind. I went back home and my Stratocaster was leaning against the wall, and I just sat there and stared at it. Probably didn’t help that I’d taken acid. But I stared at it and tried to figure out, ‘What was he thinking?’ But then I set about the task of figuring it out for myself. Other people give up. But I always think that every complex act is it’s actually just a series of small simple acts, strung together.

One of the things that happens with this band is, the power trio is more traditional in a way. I’m using effects, but sparingly I hope. In the end it still boils down to fingers on strings.

Some people won’t come to this band through Bowie or The Cure. So tell me, how would you sell this new band to my 18 year-old daughter?

Well. I would probably ask her what kind of music she likes, get her to pick some bands – then I’d probably lie and tell her our music is just the same!

Photos: Molly Hill