[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]D[/dropcap]arkly comic and no less terrifying for it, Amy Jump’s adaptation of JG Ballard’s High-Rise is timely for the British political landscape.

The author, famed for his provocative views on social construct, tells an eerily prophetic story of a modern rich and poor divide, which ultimately leads to a violent anarchy. Taken in hand by Ben Wheatley, already having marked himself an important filmmaker and as no stranger to horrific imagery, directs the moral decay to perfection.

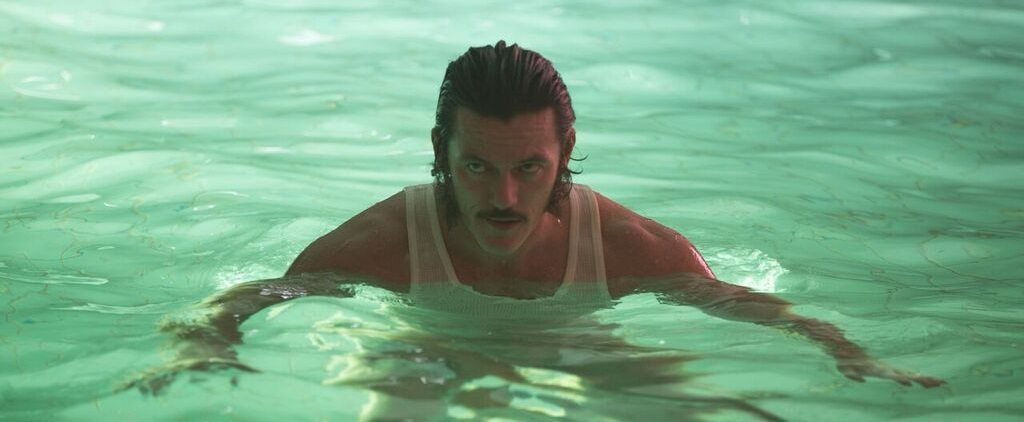

Serving as it does as a metaphor for society as a whole, the titular building is striking, the starkness of Its smooth, cool edges forebodingly overbearing in the frame. Protagonist Dr. Robert Laing (an excellent Tom Hiddleston) chooses to live in the block in a search for anonymity, his moving in told in a clean, sharply edited sequence. Taking place against the backdrop of a bustling foyer, our film’s public, it’s an effective depiction of the average person’s place in the world as a whole; a quiet acceptance of a place somewhere in the hierarchy. Here, that hierarchy is clear: the more wealthy live on the top floors, whilst the poorer occupy the low. Gradually, it becomes clear that the poor do not have the same rights within the building; electricity frequently cuts out on the lower floors alone, and their protests are met with shrugs of teething problems. A revolt spear-headed by a documentary maker (Luke Evans, wonderfully deranged) who decides to film the whole process—a neat foretelling of the social media of today—leads to complete degeneration, told in a deranged, violent sequence.

somewhere in the hierarchy. Here, that hierarchy is clear: the more wealthy live on the top floors, whilst the poorer occupy the low. Gradually, it becomes clear that the poor do not have the same rights within the building; electricity frequently cuts out on the lower floors alone, and their protests are met with shrugs of teething problems. A revolt spear-headed by a documentary maker (Luke Evans, wonderfully deranged) who decides to film the whole process—a neat foretelling of the social media of today—leads to complete degeneration, told in a deranged, violent sequence.

High-Rise portrays its social divide beautifully. The upper class’ floors and lives in the building feel an entirely different world from the one below, told via costume and set-piece to highlight the messiness of the debt-ridden poor and orderliness of the rich. Laing occupies what feels to him at first a comfortable middle, until he is shocked by the penthouse-occupying architect’s derision for the tenants in the slots he himself designed. Yet, the obnoxiousness of his richer neighbours rubs off on him; to a child, he retorts: “Why don’t you have a father?” Recognising the harshness of this statement does not quell his desire to climb the social ladder—mocked as he is for this by the self-indulgent uppers—and indeed his tenuous grasp on this will come to save his life. A particularly amusing scene shows his attempt to carry on a semblance of normalcy as anarchy takes place around him, despite his obvious distress.

The climax is a tad hammy, its use of Thatcher’s speech on the supremacy of capitalism as subtle as a sledgehammer in a film that does not need it, but the impact is held as a terrifying reflection of what feels now a not unlikely future. An important watch for all with an interest in film’s place as a sociopolitical medium.

[button link=”https://www.amazon.co.uk/High-Rise-DVD-Tom-Hiddleston/dp/B01CUEEGWG/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1468747546&sr=8-1&keywords=high+rise” newwindow=”yes”] High Rise on Amazon[/button]

Naila Scargill is the publisher and editor of horror journal Exquisite Terror. Holding a broad editorial background, she has worked with an eclectic variety of content, ranging from film and the counterculture, to political news and finance.