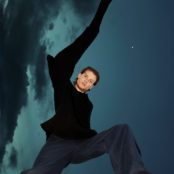

‘I’m an artist who’s interested in real issues, not just pretty shapes’

So asserts Lloyd Newson, finally cracking a veneer of measured, careful articulation that has made it nigh-impossible to come away from the Australian director/choreographer with anything worthy of an opening quote.

The problem is not that Newson is clamming up or being reticent. His views on Sharia law, middle-class cultural cringe and the after-effects of British colonialism are the contrary: strident and articulate, prompting a very papable feeeling of discomfort and disorientation on hearing them voiced publicly. You just can’t say these things, I am guilty of thinking, immediately identifying myself with the ‘left liberals’ he mentions frequently in his answers.

Left liberals who remove themselves from any civil responsibility for demanding from Muslim communities the same adherence to the mores and social norms of British society that they would demand of their own left liberal neighbours.

Perceived by many to be an exaggerated ‘greatest hits’ approach to cataloging, Daily Mail-style, the most extreme moments in the cultural growing pains between UK and Muslim societal values, Can We Talk About This? is disturbing when it turns its focus onto a well-meaning but ultimately spineless sector of society which uses the ‘live and let live’ approach to multiculturalism as a means to self-absolve their tolerance of gender discrimination, inequality, institutionalised hate-crime and expansionist proselytism by virtue of the well-worn phrase ‘it’s their culture, and it’s not for us to intervene’.

Newson, trotting out answers that flow carefully (although not quite hiding a deep anger) has all his bases covered. That deep anger stems from a personally-felt disgust at the number of Muslim countries where homosexuality is an offence punishable by death, and keeps him from regressing into robotic replies to questions which he has clearly answered before. His preparation is to be expected, and may well be what stands between him and a death warrant. As he speaks about Can We Talk About This?, I surreptitiously score line after shamed line of pencil through the series of facile questions I have prepared.

UK lawmakers no longer consult Leviticus when drafting legislation

He answers them all before they are asked. The school debating team efforts of ‘Is it not hypocritical on this, Queen Elizabeth’s jubilee, to condemn Sharia courts, given that the UK’s head of state also holds the position Defender of the Faith?’ falls foul of my churlish scratch, and I dare not ask it. Religion and state in the UK retain some nominal links, he admits. But – drawing on source material familiar to any gay rights activist regardless of their views on Islam – UK lawmakers no longer consult Leviticus when drafting legislation, a crucial point of departure from Sharia that renders angel/pinhead modes of interrogation instantly puerile and immature.

We are discussing the death and subjugation of real people, not theoretical anthropology.

Racism is quickly dismissed. Confusing an ideology or religion with a race is an unacceptable mashing of terms. One can despise an ideology with impunity, he asserts.

Grasping for an angle, Newson beats me to it again. Just as I am wondering whether he is himself self-censored, victim of the Islamophobia he pins upon those liberal progressives he is so fond of pillorying, he discourses on the very nature of that suffix ‘phobia’. Lifting a dictaphone into view he explains that every word he says about Can We Talk About This? in public is recorded, by himself. This, he explains, is so that if a fatwah were to be declared on him, it would at least have to be because of something he actually said, rather than something inaccurately reported by the press.

And right there, he said it. Fatwah. Any reporter’s guile rendered obsolete instantly. I scratch a line through ‘find out if he fears a fatwah’.

Newson’s two major themes in the piece: 1) that well-meaning liberal policies of multiculturalism have allowed UK muslims to behave in a way unacceptable to that society; and 2) that fear of retaliation has engendered a culture of self-censorship around issues related to Islam; are pinned on a paradoxical aphorism that he is at pains to elucidate.

denying them the legal rights you would demand for yourself

Racist, Islamophobic, Xenophobic? Define it. Because if by inaction, your tolerance of other cultures allows women and gays of a religious group to be openly and systematically discriminated against, you are denying them the legal rights you would demand for yourself. By extension, that is discriminatory.

Sins of omission, as Catholicism would put it.

And so, pre-empting all my questions with careful, considered (and clearly well-worn) answers, I am into my reserves. Newson mentions early on that the piece is scripted with verbatim quotations from interviewees and media sources. The interviewees are all in some way touched by an experience where extremist Muslim reactions have affected their lives, prompted them to self-censor, even in societies that honour freedom of speech.

My mother has an opinion

It is not about opinions, he states. ‘My mother has an opinion’. It is instead about experiences. I ask him by what criteria did he pick the interviewees. Newson asserts that they were all touched at ‘street level’ by extremist Muslim reactions to their words or deeds. All, he makes clear, except for a short speech towards the end of the performance from a pro-Sharia think-tank. That, he concedes, is opinion.

Why so many words and quotations in a dance piece? Why not let the dance do the talking? The veneer cracks a touch, the exasperated line about pretty shapes escapes, a chance to talk about dance, not politics.

How does one say ‘this is my brother’ through dance?, he smiles, relaxing a little at last. A concept as simple as that. Doable, certainly, but cumbersome. He is an artist, interested in real issues. And there is the critical distinction. Not the part about issues, but the word ‘artist’. Posited as a documentary, Can We Talk About This? would be guilty of personal bias and objectionable. As the vision of an individual artist though, it is as legitimate as Picasso’s singular vision of the Guernica bombing, on permanent display just a few blocks south of tonight’s performance.

How the piece relates to a Spanish audience is interesting, and by now the only worthwhile point of interrogation in a show which made its London debut late in 2011. Speaking before the show, the word ‘fascism’ is casually dropped by the Spanish interpreter. The context uses the word negatively, as it would be accepted instantly by a UK audience.

In a town which remained the capital of a fascist dictatorship until as recently as 1975 though, where the national police force retain the axe/bundled sticks symbol of fascism on their insignia; where the gargantuan tomb of Generalissimo Franco is protected by an eternal police vigil; and where the almost Shakespearian phrase ‘fuera moros’ (‘Moors Out’) can be seen graffitti-tagged onto bus shelters nationwide, it’s not so clear that the word be accepted here as universally damning.

Later, watching the packed-out theatre applaud (three curtain calls, standing ovation), I’m tempted to wonder if some of the adulation stems from a ‘Borat effect’. The moment in that character’s film where he garners whooping validation from a rodeo crowd for claiming that he hopes George Bush will drink the blood of every man, woman and child in Iraq? I worry that a condemnation of Islam, filtered through Spanish-language subtitles be taken at face value, the subtleties ignored. Thankfully, I don’t believe that was the case in Madrid.

a stage-based framework that works perfectly

Can We Talk About This? is a fiercely strong piece of physical theatre, which manages to place the visuals of dance, and a script of political interrogation, into a stage-based framework that works perfectly. In large part, it is the outstanding quality of the dancers and choreography that elevate the piece above the sledgehammer media manipulation of, say, Stone’s JFK. Being able to depend on dancers to deliver a line whilst crawling lizard-like across a floor or balancing on their head without appearing absurd, makes for an enticing experience.

Critical reaction to the piece has concentrated on Newson’s approach, rather than any flaws in the performance – The Guardian’s Sarfraz Manoor provides a concentrated precis: ‘Its linear structure and the lack of light and shade seems more akin to a polemical lecture than a piece of theatre….no examination of the role class may play in the formulation of cultural conservatism among Britain’s Muslim community. Nor did the show ask why it is only in the last three decades that this political Islam has flourished’. A fair comment. Nevertheless, politics aside, the dancing is superb.

That Newson can call upon his dancers to convey sarcasm by their movement alone, is a talent of which he makes ample use. Modern dance, defined and sometimes derided for its acknowledgement and use of gravity and groundspace, nevertheless affords some moments of balletic grace to Newson’s work – a dancer conveys the impression of being interviewed on a comfortable couch, shifting position and casually lounging, despite the ‘couch’ being another dancer holding her aloft.

the erotic charge of physical subjugation

Chase and confrontation scenes are deftly managed; tragedy, fear and anger are fluently translated into physical movement; the erotic charge of physical subjugation is a subtext of his male-female domestic confrontations. If Newson’s political message is blunt (and it is actually not), his capacity to convey complex emotion, sardonic meta-narrative and emotional punctuation to verbatim dialogue via dance is world-class.

So much so that, watching, alarm bells tinkle in the back of my mind. Particularly at the point where I find myself nodding in agreement with a David Cameron speech condemning UK multiculturalism policies. A piece of art which prompts me to agree, even temporarily, with ol’ condom-face needs to be treated cautiously. There is always something of a Nuremberg reflex in great theatre.

Here in Spain, much of the hand-wringing political and quasi-political discourse of Can We Talk About This? is without a local parallel; not least the local politician’s fear of a vote-losing backlash that ghosts the narrative from time to time. Spain, where multiculturalism is accepted more grudgingly than in polite middle-England, entertains none of the kid-gloves approach.

Citizenship and Spanish Language are compulsory subjects for the entirety of the school career (including private and international schools), non-nationals are distinguished by an ‘X’ prefix on their (compulsory) national identity document. Registering to vote, whilst technically a right for non-nationals, is rendered effectively impossible by a series of bureaucratic Catch 22s.

When my local librarian admonishes children for talking in Arabic, the very conundrum that Newson examines becomes manifest. Shush them by all means – this is a library – but for talking in Arabic? Can you do that?

So how will that liberal, progressive flinch be felt by a Madrid audience, in a country whose reaction to recent economic crisis was a landslide electoral victory for the right-wing Partido Popular? I’m almost certain that the man sitting two seats to my right is Pedro Almodovar, whose films went a long way toward defining and voicing the cultural values of the immediately post-Franco Madrid ‘movida’ in the late 70s. I have an eye on his reactions, and on those of the audience as the performance unfolds but, truth told, the action onstage is so consistently compelling that it is a waste to concentrate on anything else.

A notable intake of breath occurs when a protest banner is recreated onstage calling for a 9/11 in Spain (as well as other countries which supported the second Gulf War). My train home later that evening pulls to a halt at Atocha’s Platform three, where an Al Qaida train bomb killed 191 people in 2004. Death is universal.

You always think of something clever to say after the argument has finished, and Newson’s quote-montage technique is sometimes a little like amalgamating all the clever soundbytes for his own side of the argument and leaving the ill-advised, self-contradicting, and immature extremism of his adversary exposed. But then, in what context are death-threats, sanctioned murder or institutionalised sexual discrimination acceptable? Dredge hard, you may have an answer to that. Add the further question: within the legal framework of the UK?, and it becomes more difficult to address.

the tentative liberalism of marginal-seat politicians

That a well-meaning series of initiatives to combat racism and promote social cohesion became the framework by which 85 Sharia courts now exist in the UK; or that the tentative liberalism of marginal-seat politicians has created a culture of tolerance that makes Britain an attractive destination for extremist preachers (of all denominations) is, when watching Can We Talk About This?, an obvious absurdity. Away from the lights and the magic though, it is hard to dismiss so easily. Is not an abandoning of that historical tolerance a capitulation to the very terrorists who exploit it? The question is touched upon in the performance, but it is one of the rare moments where Newson fails to adequately express an answer.

Or, for a piece which was partly inspired by Muslim attitudes to homosexuality, where are the stories of Muslim gays and lesbians in the performance? Newson mentions that the words of one lesbian protagonist appear in one of the vignettes, but in the play they are not flagged as such. That demands explanation – are issues of sexual orientation irrelevant in the more general context of human rights abuses, or is Newson reluctant to examine them for other reasons? If the latter, it would be good to know what those reasons are.

the most spectacular piece of theatre I have ever experienced

And yet, re-reading this review, I am bemused to see so much attack in my prose. Attack on a performance which, truth told, is the most spectacular piece of theatre I have ever experienced. That dance/physical theatre – a medium unaffected by digital piracy and the creative conservatism that phenomenon has prompted in other artforms – displays innovation, should not and does not surprise me. That it can in 2012 still be revolutionary, nearly a century after J.M. Synge‘s The Playboy of the Western World incited mobs to riot on entirely unrelated provocations, is an unalloyed delight.

Just as Newson is perfectly prepared for accusations of inaccuracy, bias, intolerance, racism or sensationalism before the play starts, so too is the performance prepared. The quotes used may be taken out of context, recontextualised in a hostile environment, isolated. Nor do they reflect the lives or values of a vast number of Muslims, or claim to. Nevertheless, the fear portrayed is real, the events real, the establishments portrayed, real. The sheer bravery of Newson and cast for performing the piece is as genuine a piece of human valour as you will witness.

And to obscure any of that simply because I am a little piqued to be numbered amongst those who would prefer to keep my head down, say ‘well, it’s not right to impose my moral values on another culture’, would be unforgivable. Newson’s contempt for that mode of thought exposes my own moral cowardice, and in petty retaliation I have spent too much effort searching for minor negatives – observing that the in-audience actor protesting against the piece fooled no-one; finding the dialogue rushed and indecipherable at moments – these are the reflexive flinches of a critic who feels snubbed.

Because although ‘left liberals’ are a focus of the piece, Newson does not even dignify us with the anger he reserves for extremists. We flaccid handwringers are simply thrown scraps of scorn, disdain, and that ever-impressive sarcastic dancing. Can We Talk About This? Emphatically so. Probably for decades.

Teatros Del Canal, Madrid. June 2nd 2012

Sean Keenan used to write. Now he edits, and gets very annoyed about the word ‘ethereal’. Likely to bite anyone using the form ‘I’m loving….’. Don’t start him on the misuse of three-dot ellipses.

Divides his time between mid-Spain and South-West France, like one of those bucktoothed, fur-clad minor-aristocracy ogresses you see in Hello magazine, only without the naff chandeliers.

Twitter: @seaninspain